Wetlands and us

From the earliest civilisations to the ancient traditions of indigenous people, we have relied on them for food, water, shelter and medicines.

Today it seems we need them more than ever, for our health, our happiness and our wellbeing.

A connection as old as time

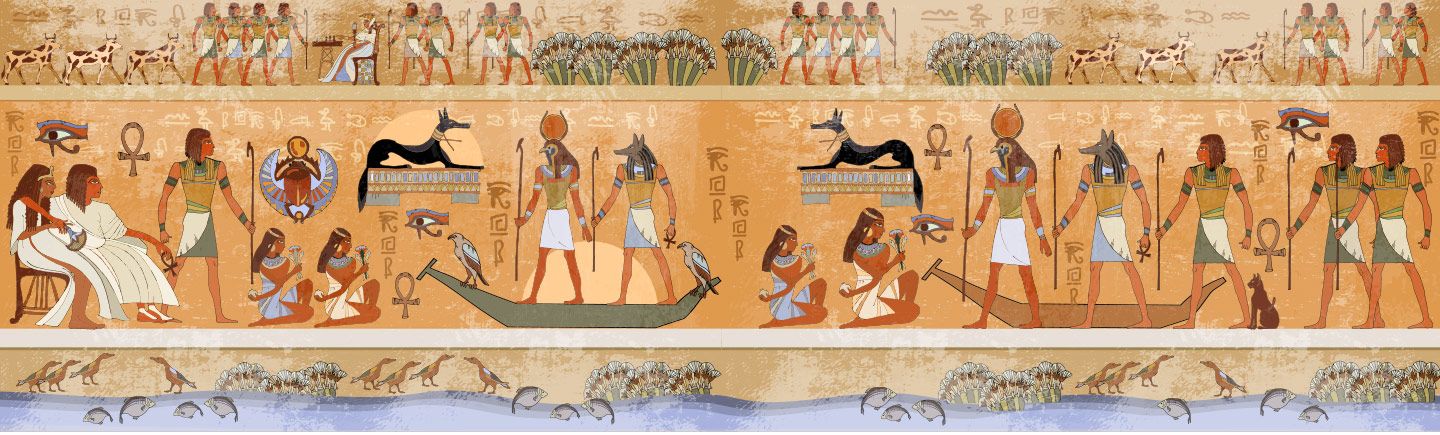

Through the largest, driest desert on earth flows the shimmering blue life-force of the Nile River. For almost 3,000 years this great river was home to one of the most powerful civilisations in the world. The fertile waters of the Nile, and its surrounding wetlands, allowed the people of Ancient Egypt to thrive in the gruelling climate.

They relied on the Nile for freshwater, food and transportation. Its seasonal flooding gifted them with fertile land to farm on. Every August, when the river burst its banks nutrient-rich soil carried in the water spread across the river banks, coating the land in a thick, moist mud (silt) which created the perfect conditions for growing crops.

River Nile, Sudan It is easy to see from this image why people have been drawn to the Nile River in Egypt for thousands of years. Green farmland marks a distinct boundary between the Nile floodplain and the surrounding harsh desert. Photo by USGS on Unsplash

River Nile, Sudan It is easy to see from this image why people have been drawn to the Nile River in Egypt for thousands of years. Green farmland marks a distinct boundary between the Nile floodplain and the surrounding harsh desert. Photo by USGS on Unsplash

The wealth of Ancient Egypt depended on success in agriculture: they developed irrigation systems, ways of storing excess food and the river allowed for plenty of trading opportunities. Over time, it is estimated that the river supported more than three million people. With less time and energy taken up with basic survival, people began to develop other skills like craftsmanship, art and architecture. Thanks to the life-giving wetlands of the Nile life became easier, people made money and over time wealthier members of society had the luxury to develop more cultural pastimes. The artistic and architectural legacy of Ancient Egypt remains today.

Since these very first civilisations the fortunes of wetlands and humans have been inextricably linked and they remain so today. That wetlands are essential for us to live is indisputable, they sustain the wide variety of life on our planet, protect our coastlines, create natural sponges against flooding, provide clean water and fresh food and store carbon to regulate climate change. On a purely practical level humans need the services wetlands provide to survive.

According to Ramsar – the international body for the conservation of wetlands and their resources – more than a billion people live on or around wetlands.

“These benefits, known as ecosystem services, are the benefits people get from nature. As we degrade wetlands, we erode these benefits leading to a decrease in the quality of our own lives. It’s the poorer people in lower-income countries who suffer first, those who live in places where technological solutions are not as readily available to replicate the natural benefits that come from wetlands.”

But humanity’s connection with wetlands goes deeper than just the resources we can take from them.

A deeper connection to nature

On the edge of the world the midnight sun fills the lakes and waterways with an amber glow. A group of reindeer herders move across the frozen arctic towards their next stopping point.

It’s a place they know well, this land as familiar as the back of their hand. An instinctive knowledge passed down by generations and absorbed by the children that accompany their parents on the 400-800 mile journey every year. As the reindeer make their way from the summer pastures of the north to the winter pastures further south temperatures will sink to -40c. It’s a hazardous journey that requires a symbiotic relationship between reindeer, people and nature. They must cross huge frozen rivers in the right place at the right time, they must know where to find food, water and places to rest. At times it is unclear who leads who.

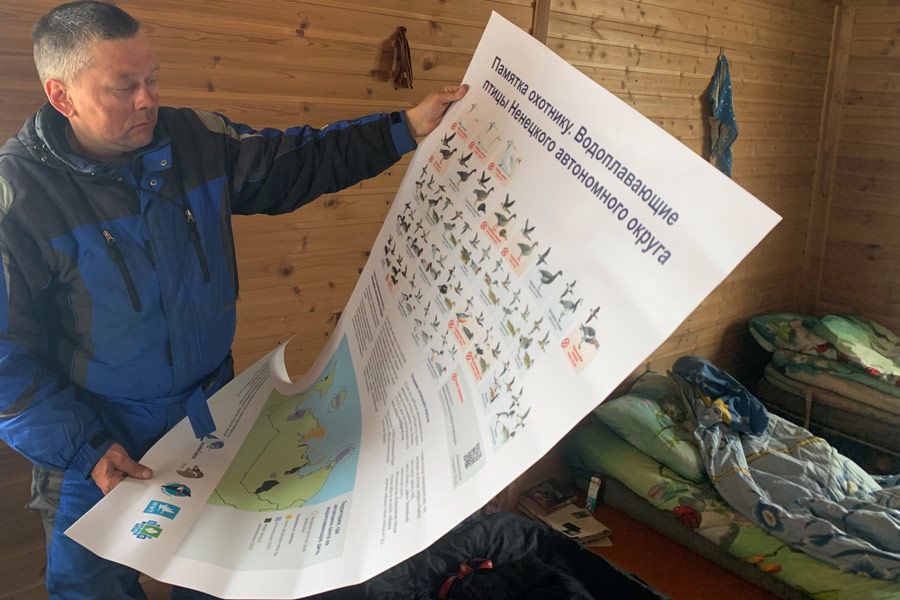

Vladislav Viucheiskiy is one of thousands of herders that live here, along with 255,000 reindeer. As head of the Reindeer Herders Union of the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, he knows that being attuned to nature in this way is intrinsically linked to his people’s survival. As Vlad herds his reindeer across the vast tundra wilderness, he’s following in the footsteps of his ancestors going back thousands of years. His is largely a nomadic life, following the seasons, and it’s only his knowledge of the tundra wetlands, learnt over a lifetime and handed down through generations, that enables him to sustain him and his family in this seemingly hostile place.

Vladislav Viucheiskiy

Vladislav Viucheiskiy

“Throughout the ages, the indigenous people of the Arctic north have believed that caring for the environment is fundamental to survival. By observing and imitating the habits and behaviour of the arctic and its wildlife, we have learnt how to survive and endure the harsh conditions we live in.”

You may think of the Arctic as an empty, frozen space, but 60 per cent of it is made up of wetlands with communities across the Arctic depending on them for survival. The Nenets depend heavily on their reindeer herds, using them for food, clothing, tools and transportation. In return they have lived on and stewarded the tundra's fragile ecology for hundreds of years.

Vlad is one of 370 million indigenous people across the world, many of who share an intimate relationship with their lands. The Noongar – Aboriginal people of south-western Australia – describe the wetlands they call home as their ‘beating heart’. Their ancestors travelled across these lands fishing for crayfish and turtles and collecting wild onions, potatoes and carrot. The wetland provided everything they needed and they knew where to find it. ‘The heart keeps you alive,’ they say as the wetland provides.

Indigenous peoples may only make up 5 per cent of the total world population but they officially hold 18 per cent of the land and lay claim to far more.

Their homelands span 70 countries from the Arctic to the South Pacific and includes many of the planet’s biodiversity hotspots. Indigenous land hosts 80 per cent of the world’s land-based biodiversity, we must consider them critical guardians of our natural world. Their traditions and belief systems often mean that they regard nature with deep respect, and with that comes a strong sense of place and belonging.

Today climate change, development and urbanisation are eroding the lives of many indigenous communities across the world. As these ancient ways of life disappear we lose not only vital knowledge about our natural world but also an opportunity to learn how to coexist in harmony with nature.

Are we losing a unique connection?

These spiritual and emotional connections exist for all of us on some level, although we may not be aware of them. And these connections seem to be even deeper around water.

Those who have delighted in the rustle of the reeds over a marshland, felt invigorated by a windswept beach or sought out the wise whisperings of a meandering river, know that water is about far more than our physical health. It’s something that, as humans, we are naturally drawn to. Some argue that we have an innate connection to water. Human foetuses still have gill-like structures in their early stages of development, we spend our first nine months of life immersed in the watery environment of our mother’s womb. When we’re born, our bodies are approximately 78 per cent water. As we age, that number drops to below 60 per cent but our brains continue to be made of 80 per cent water.

This connection with water is something we seem to need. At their most basic wetlands are about survival for all living species, but it is clear to many of us that they support our mental health and our wellbeing too, that they provide a connection to our past and a lifeline for our future.

But it seems our modern-day life is making it harder for us to access these watery places that we need most, with disastrous implications.

Today most of us live in urban environments, where we have little access to green space, let alone blue space. Our towns and cities are developing rapidly, often with very little thought for nature. According to the United Nations 68 per cent of us will be living urban lives by 2050.

But this increased disconnection to the natural world creates problems for all of us. At the same time, we live in a society where record numbers of people are being diagnosed with depression, anxiety and stress. According to The World Health Organisation, depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide and a major contributor to the overall global burden of disease. Economically, these chronic diseases place a huge burden on our health and social care services. NHS England spent £11.9 billion on mental health services in 2017/18 alone.

NHS England Annual Report

NHS England Annual Report

Children and their connection to nature

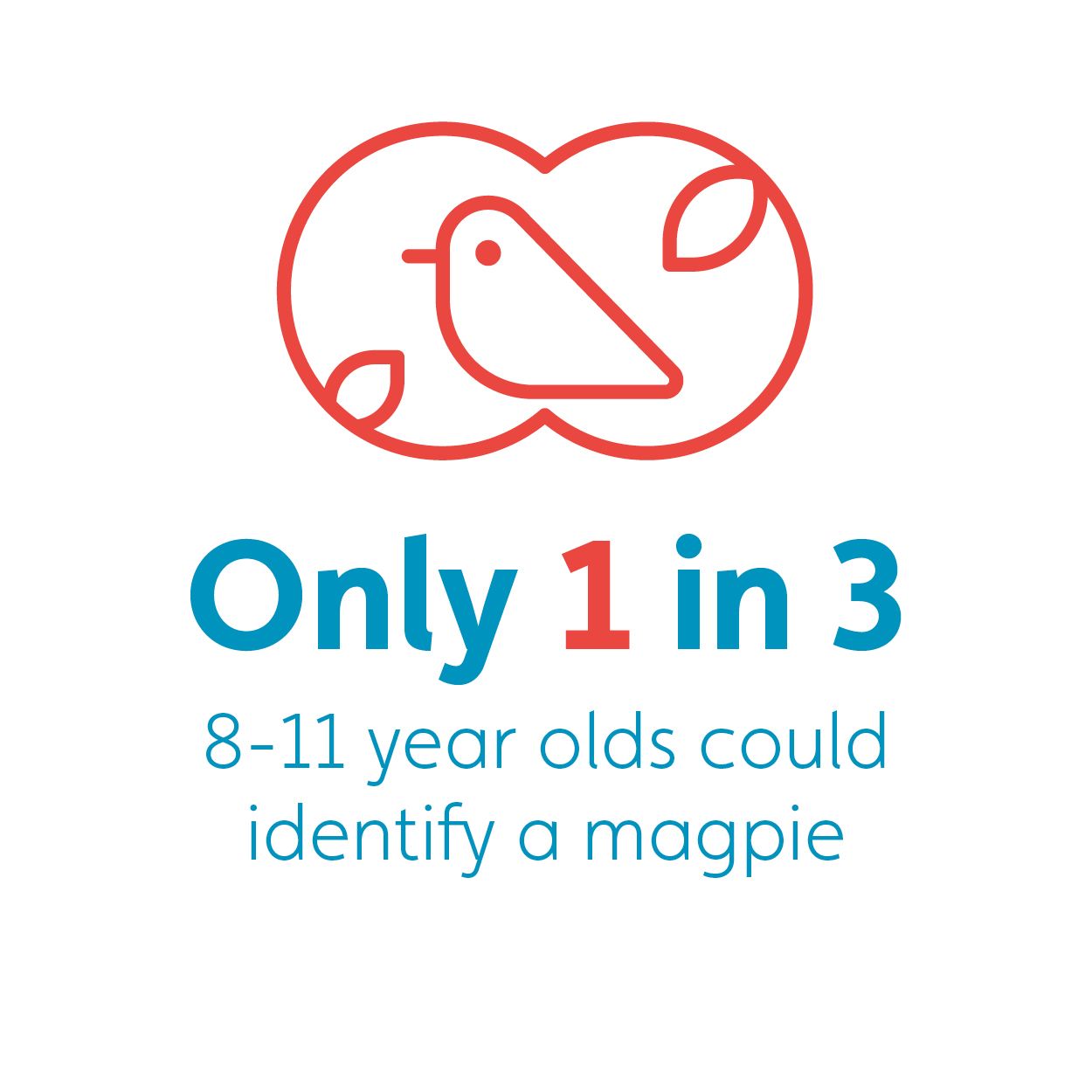

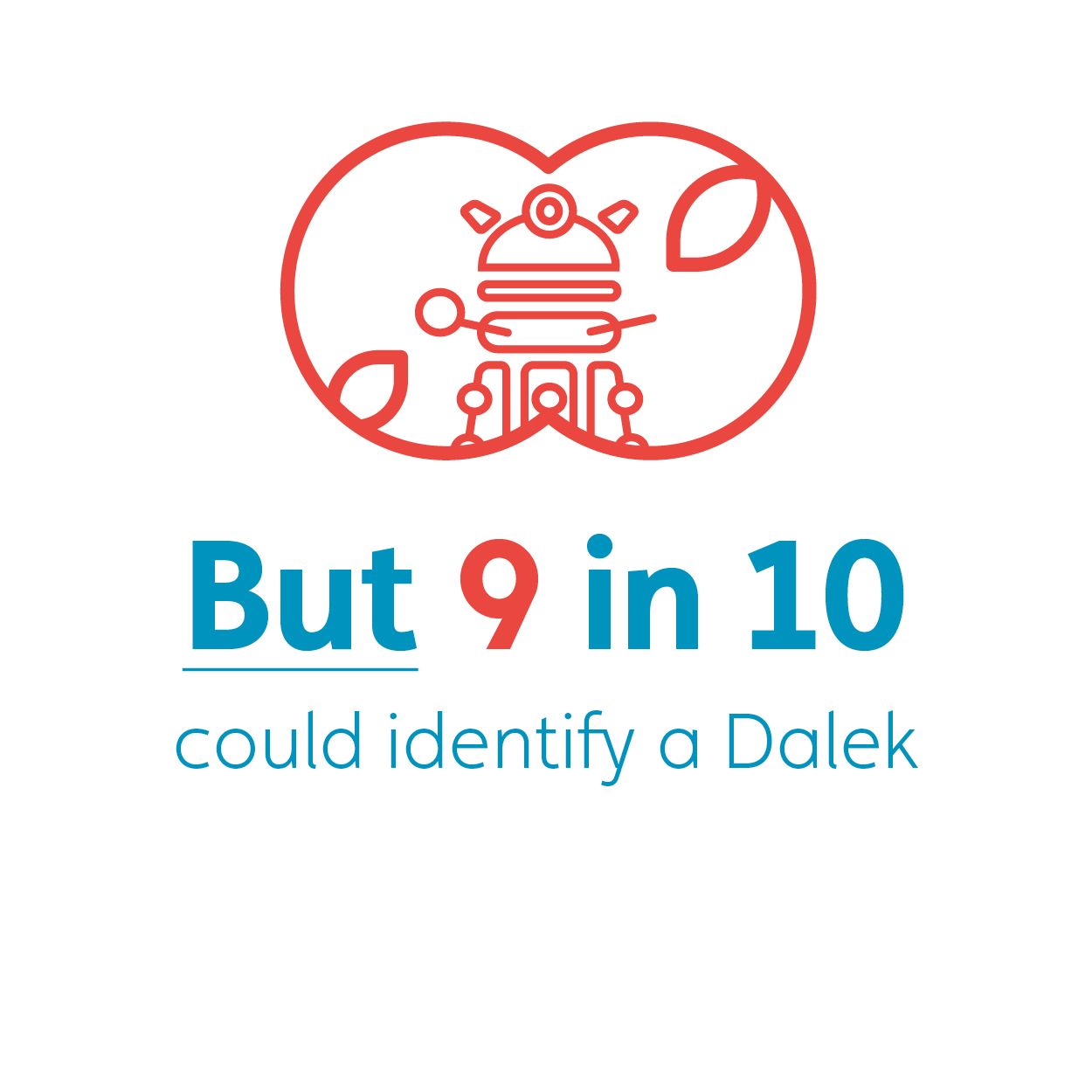

Most alarming is perhaps the lack of connection that many children seem to have with nature. A study by Cambridge University has shown that kids know more about Pokémon characters than the names of trees growing in their area. And a National Trust survey concluded that only a third of eight to 11-year-olds could identify a magpie (though, of course, nine out of 10 could name a Dalek).

National Trust Survey 2017

These trends have implications not only for the health of future generations and their connection to the natural world, but also their ability to protect it.

National Trust Survey 2017

“There’s increasing evidence that taking part in activities in natural habitats helps children to develop creativity, imagination and spatial awareness. It can also have a positive impact on their self-esteem and confidence. Worryingly, studies suggest that if children lack direct contact with nature, they are much less likely to care for it and take action to protect it”

In his book Last Child in the Woods, author Richard Louv coined the phrase ‘Nature-deficit disorder’ to describe the human costs of alienation from nature. He cites diminished use of the senses, attention difficulties, and higher rates of physical and emotional illnesses as key components.

“Without that connection to nature, people lose interest in protecting it and fail to see how connected it is to our lives — our food sources, our climate, our quality of life.”

National Trust Survey 2017

National Trust Survey 2017

National Trust Survey 2017

National Trust Survey 2017

The healing power of nature

It’s a bright, cold morning on Watergate bay in Cornwall. A group of 20 young people are bobbing about on the sparkling blue of the sea waiting for the next wave to come in. They’re having a surfing lesson. Each one of them has been diagnosed with a mental health disorder. Some participants have been self-harming, others experience severe anxiety, low mood or depression. One has recently been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Yet watching them out on the water, you’d never know.

The Wave Project was started in 2010 as a way to help young people suffering with mental health problems. The six-week surfing courses are completely transformative. Whatever negative emotion a young person enters the water feeling by the time they emerge their outlook on the world has totally changed.

Last year DEFRA commissioned the University of Exeter Medical School to examine the results of individual research projects on the effects of being outside in nature on our health and wellbeing. The report concluded:

“There is strong and consistent evidence for mental health and wellbeing benefits arising from exposure to natural environments, including reductions in psychological stress, fatigue, anxiety and depression.”

Could our natural world be the answer?

Last year The People & Nature Survey for England 2020 found that 85 per cent of adults reported that being in nature made them happy. This was consistent across different population groups. Nature provides many things that help human beings to live healthier and happier lives. These can be direct influences, literally creating biophysical changes to our environment that benefit us, such as regulating air temperature. But they can also be indirect, simply providing peaceful environments that require little concentration and provoke minimal stimulation so enabling us to rest our tired, overworked brains. You might know it as ‘a little peace and quiet’.

Nature also encourages us to be socially engaged and physically active, and when outside we take deep breaths of fresh air and absorb vitamin D. Our affinity with water suggests that wetlands are especially important in the nature-health interaction.

A recent study conducted by researchers at the University of Exeter found that approximately 271 million recreational visits are made to coasts and beaches each year.

Studies show that being close to water has many positive markers for physical and mental wellbeing but it seems people are discovering this for themselves.

According to the Outdoor Swimming Society over 7.5 million people are now swimming regularly in open water and outdoor pools. It’s a trend that has gained serious momentum over the last few years and the people that do it need no convincing that it’s as great for their health as it is for their wellbeing.

Outdoor Swimming Society

Outdoor Swimming Society

Once a week Sophie Nioche, 43, an environmental planner from Bristol, leaves her desk for a swim in a wild lake.

“I really look forward to it,” she says. “I’m there rain or shine, summer or winter. Whatever my mood going in, I always come out of the water feeling uplifted, invigorated and calm. I’m sure it boosts my immune system too because I’m rarely unwell.”

The evidence is mounting that cold water swimming in particular is not only good for our physical health but our mental health too. Last year a paper was published in the British Medical Journal detailing the journey of a 24-year-old woman who had taken antidepressants from the age of 17 to treat anxiety and depression. After the birth of her daughter she wanted to be medication-free and began outdoor swimming in 15°C water. Her mood improved immediately, she gradually weaned herself off antidepressants and a year later she remained medication free.

Wetlands improve mental health

It’s a normal spring afternoon at WWT Slimbridge wetland centre and visitors are enjoying the first warm sun of the year. But for one group of people there’s nothing normal about this day, because for some of them this is the first time they’ve been out of the house for several months. They are part of a pioneering project monitoring the effects of wetlands on mental health. Each person has been diagnosed with anxiety or depression and have signed up for a ‘blue prescription’.

Six weeks later researchers found that the participants experienced significant reductions in stress and anxiety, and their mental health assessment improved from ‘below average’ to ‘average’ by national norms. One participant said: “It has improved my mental and physical health being in nature with care and support. The staff have been very kind and generous and I feel bolstered to have this experience when going through a difficult time.”

WWT has now partnered with the Mental Health Foundation to make the Blue Prescriptions Project a reality.

“If people are experiencing poor mental health it can be incredibly difficult to leave the safety of your home and get outside,” explains Jolie Goodman, programmes manager at the Mental Health Foundation.

“If you have grown up in a city you may not feel safe in nature particularly when life is challenging. The Blue Prescriptions Project will combine being outside in WWT sites with a structured course to support people to prioritise looking after their mental health,” she says.

Wetlands support our wellbeing

Most scientific research so far has focused on the benefits of green spaces or coastal areas, with wetland habitats often being overlooked. Researchers at WWT are working to fill this knowledge gap and understand the relationship between human health and wetlands.

Last year WWT researchers completed a pioneering research project at London Wetland Centre with Imperial College, London. The team worked with 36 healthy participants who moved between the wetland, urban and control settings while continuously wearing a headset (to measure surface brain electrical activity, EEG), and a wristband (to measure physiological stress responses, heart rate variations and skin activity).

The research team also used questionnaires to measure how the participants rated their mood in each setting. Following the questionnaire, people self-reported that 10 minutes in the wetland setting led to an increase in positive feelings, but those who were more stressed felt greater benefit - they experienced decreases in negative feelings as well.

“We know nature is good for us in many ways, from hastening recovery time from illness to improving self-esteem. Wetlands provide a setting not just for physical exercise, but for relaxation and restoration. Our work indicates that spending time in wetlands can help reduce anxiety and stress.”

Stress, depression and anxiety represent one of the UK’s biggest health challenges accounting for 40 per cent of GP appointments and affecting 1 in 4 people each year. In England, 1 in 6 people report experiencing a common mental health problem (e.g. anxiety, depression) in any given week. This costs the NHS over £34bn a year with the wider economic, social and health costs amounting to £105bn per year.

According to Natural England, the use of nature-based health solutions could reduce outpatient admissions by a fifth, save time for GPs, and achieve significant cost savings. It found a return on investment of £3.12 for every pound invested in nature-based healthcare. Overall, by harnessing the restorative power of nature, billions of pounds could be saved each year for the NHS, as well as improving quality of life and health for patients.

That human beings need nature is no longer in question, rather ask yourself how can we live without it?

Salt Hill Stream, Slough

The Salt Hill Stream, which runs through the heart of Slough, was in terrible health. Fish were dying. It was clogged up with old car tyres, carrier bags and household waste. Water quality had deteriorated and its future looked bleak.

WWT began working with the local community back in 2014, breathing new life into the neglected stream. Although restoring urban streams to good ecological health takes a long time, the Salt Hill stream project shows that, with the community behind you, they can become spectacular wetland sanctuaries for people and wildlife.

And if designed properly, they can also help us tackle pollution, protect us from flooding, improve water quality and support the wellbeing of the communities around them.

Daniel Barduille, 55, was a volunteer on the project. He explains how it has impacted his life.

“I’ve been out of work for some time so I thought I needed to do something that had nothing to do with signing on. I thought it would be a good thing to do off my own back. It was an outlet for me to do something independent. It’s empowering. People come up and thank us for what we’re doing. It’s a great sense of reward. You can’t beat it.”

Daniel Barduille

Daniel Barduille

As part of the project new floodplains and new wetlands were also created. The stream and its surrounding area supports dragonflies, frogs, colourful meadow flowers and birds. In the long run it will help store floodwater, filter pollution and provide homes for all sorts of wildlife, making it the perfect place for people too.

This project has helped people connect with others and ensure local communities develop a lasting affinity with the stream and its catchment. It has enabled people to give to others through volunteering, learn new skills to improve their local environment and appreciate the environment around them. It supports people to be physically active and facilitates mindfulness (the ability to pay attention to the present moment).

What’s next for our relationship with wetlands?

The world is facing a climate crisis, a nature crisis and a wellbeing crisis. The causes of these are complex but they are certainly linked.

That our health is intrinsically linked with that of our planet is something we can no longer deny. Each one of these issues is compounded by wetland loss. Globally we have lost 35 per cent of freshwater wetlands since 1970 but we don’t depend on them any less – they’re still essential providers of many goods and services. There’s no way we can address the depth of the crisis humanity is facing without reinvesting in our wetland resources.

The last year has brought into sharp focus the need to ‘build back better’. With an end in sight to the global pandemic that consumed 2020, 2021 gives us an opportunity to do this.

In June of last year Dr Maria Neira, Director of Environment, Climate Change and Health at the World Health Organization, said:

“The world has gathered around one goal: the race to zero deaths from COVID-19. A healthy recovery from this pandemic means we need to continue and expand this race to zero deaths from climate change and environmental pollution, a race to zero people pushed into poverty because of health costs, to zero people breathing polluted air.”

The UK government has said it wishes to, ‘act wisely to lay in place new long-term foundations…as previous generations built infrastructure on which the public now depend’. This approach must surely include making better use of natural infrastructure.

The government recognises the value of connecting people with nature to improve wellbeing but accessibility is a problem. Most of us live in built up areas and in the UK 1 in 8 families don’t have access to their own garden (1 in 5 in London) and in England black people are nearly four times as likely as white people to have no access to outdoor space at home.

The government aims, for more people, from all backgrounds, to engage with and spend time in green and blue spaces close to where people live and work, particularly in urban areas and encouraging more people to spend time in them to benefit their health and wellbeing.

Wetlands already exist as a part of many urban environments – think of canals, rivers, streams, ponds, and lakes - but they are often in a poor condition and we need to make better use of them. Wetlands are also easy and cheap to create – garden ponds, rain gardens, fountains. These blue spaces will all support wellbeing and by creating accessible and attractive blue spaces where people live and work, you can target areas in the greatest need.

A plan for the future

As the world’s leading experts on wetland regeneration WWT have already begun this important work but to make far-reaching and sustained changes, support from government, big business, local communities and individuals is essential. Everyone can play a part.

In the Blue Recovery proposal WWT proposes, creating 100,000 hectares of wetlands to help address the climate, nature and wellbeing crisis and to help the UK recover from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Many communities across the world have benefitted from wetland creation, however there is potential to do much more. WWT believes that as a society, we need to move from ad-hoc interventions to creating a strategic network of wetlands.

Each of these wetlands will have individual benefits for the communities they serve but together they will provide:

- A carbon storage network, using wetlands to sequester and store carbon

- A flood management network, using wetland features to reduce flooding

- An urban wellbeing network, using wetlands to improve wellbeing

- A water treatment network, using wetlands to support biodiversity

WWT proposes to do this by restoring and creating existing wetlands, supporting individuals and organisations to create wetlands and helping local people to look after and value wetlands.

“The most effective way to save the threatened and decimated natural world is to cause people to fall in love with it again, with its beauty and its reality.”

By surrounding ourselves with nature, we learn to care more about it. At this crucial juncture in time we underestimate our innate connection to the natural world at our peril.

Reference

University of Exeter blue health research

What impact do seas, lakes and rivers have on people's health?

Defra/University of Exeter report on health benefits of being by the sea

© WWT images. Shutterstock/iStock/Unsplash/Stocksy