Wetlands and art

Artists have always been inspired by nature. But could they also have a role in helping protect our planet and its biodiversity?

Inspirational wetlands

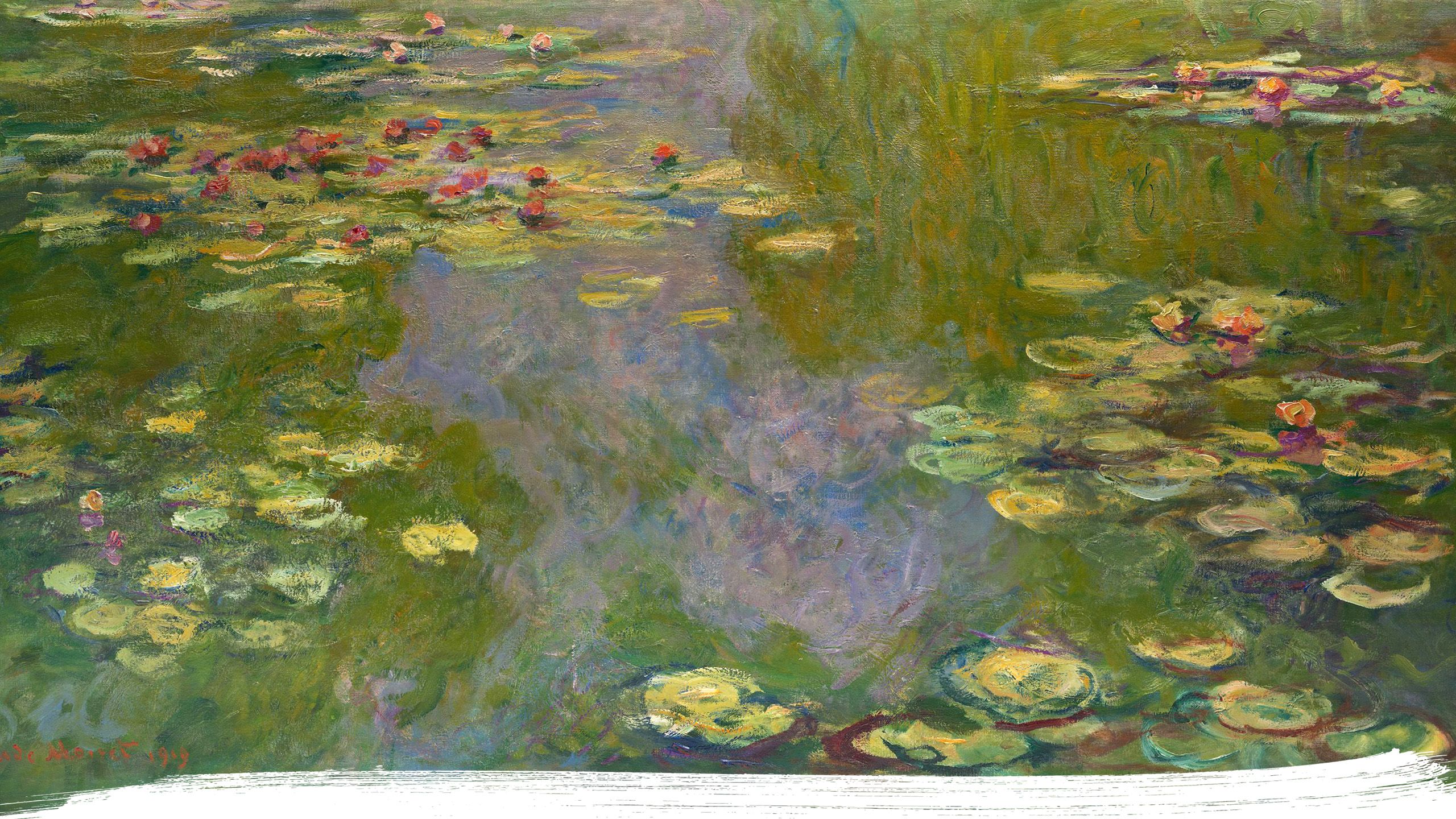

The sights and sounds of our wetlands - our estuaries, rivers, lakes and ponds - have provided inspiration for artists throughout the ages. Think Turner’s oils and watercolours that capture the play of light on water over Venice’s lagoons, or Monet’s lilyponds.

Turner made just three short trips to Venice in his lifetime, but he produced hundreds of drawings and watercolours while there, which had a profound impact on his later oils. Turner’s Venetian views are among his most acclaimed and successful works.

Venice, from the porch of Madonna Della Salute, Joseph Turner. 1835

Venice, from the porch of Madonna Della Salute, Joseph Turner. 1835

Creating a lasting impression

Water lilies were a huge novelty in Monet’s time. After seeing them in an exhibition, he fell in love with their exotic perfection. He was so inspired he enlarged his existing pond at his home in Giverny and filled it with water lilies. He also built a humpback bridge at one end, influenced by examples from Japanese prints.

These lily ponds became the main focus of Monet's later career. He was obsessed with these landscapes of water and reflection and with capturing them on canvas. After the horrors of the First World War, they offered a welcome retreat into a world of tranquil beauty that he returned to time and time again.

Monet painted more than 250 pictures over the course of his last thirty years. His water lilies have since come to be regarded as some of the most iconic images of impressionism.

A place for imaginations to run wild

Authors and poets have also been stirred by the beauty of wetlands and their wildlife to create places where our imaginations can roam. For some like Arthur Ransome and his Swallows and Amazons, set on the Norfolk Broads, they’ve offered places for adventure and exploration.

The Norfolk Broads, the setting for Swallows and Amazons.

The Norfolk Broads, the setting for Swallows and Amazons.

For others, they’ve provided the inspiration to create friendly stories full of colourful characters, like Beatrix Potter’s beloved Peter Rabbit, Jemima Puddleduck, Jeremy Fisher and Mrs Tiggywinkle, born out of her family holidays to the Lakes.

A real-life Jeremy Fisher, minus galoshes and macintosh!

A real-life Jeremy Fisher, minus galoshes and macintosh!

And whose childhood hasn’t been left enchanted by the adventures of Tarka the Otter and his life in a Devon river, or by the description of Mole’s first sighting of the river in Wind in the Willows.

‘Never in his life had he seen a river before – this sleek, sinuous, full-bodied animal, chasing and chuckling, gripping things with a gurgle and leaving them with a laugh, to fling itself on fresh playmates that shook themselves free, and were caught and held again. All was a shake and a-shiver – glints and gleams and sparkles, rustle and swirl, chatter and bubble.’

For others, it’s the vast landscapes and wild vistas of our estuaries and the haunting calls of the birds that live there, that have captured hearts and fed imaginations.

From Yeats’ ‘He reproves the Curlew’, to Dylan Thomas’ poem ‘Over Sir John’s Hill’ that celebrates the views over his beloved Taf Estuary in Wales, these wetlands have stirred a range of responses.

In 'He reproves the Curlew' an escape to the sanctuary of nature is tainted by the sorrowful call of our largest wading bird, causing the narrator to cry...

The depths, expanse and wilderness of the Lake District, have been a huge influence on some of England’s best-known writers, in particular the Romantic poets of the late eighteenth and nineteenth century.

Poets from this time, including William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and John Ruskin were inspired by the lush environment of water, forests, and fells. William Wordsworth lived near Grasmere and his poem ‘Daffodils’ beginning ‘I wander’d lonely as a cloud’, is the quintessential Lake District poem. While John Ruskin lived near Coniston and Samuel Taylor Coleridge moved his family to Keswick.

In contrast, our coastal wetlands have inspired very different affections. Who can forget the mysterious and mist shrouded mudflats and saltmarshes, so evocatively captured in the opening lines of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations.

‘Ours was the marsh country, down by the river, within, as the river wound, twenty miles of the sea.’

For Pip it was an otherworldly place…

‘.....a dark, flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dikes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it.’

More recently, Delia Owen’s novel Where the Crawdads Sing, which has now been made into a film, is set in the mysterious network of saline lagoon, swamp, and marshland on the North Carolina coast.

There is beauty in the descriptions of this wild, overlooked landscape where Kya the ‘marsh girl’ lives. But also a sense of isolation, desolation and poverty. Of a life lived on the margins and of a place that offers invisibility to society’s outcasts.

‘Please don’t talk to me about isolation. No one has to tell me how it changes a person. I have lived it. I am isolation.’

The remote beauty of the coastal marshes featured in Where the Crawdads Sing.

The remote beauty of the coastal marshes featured in Where the Crawdads Sing.

In Star Wars, the foreboding swamps and forests of Dagobah are where Jedi Master Yoda returns, to live in exile after the Empire's rise. And it's to this remote world that Luke Skywalker travels, to be trained by Yoda in the ways of the Force.

Even in gaming culture, the unearthly nature of our swamps, marshes and mangroves provides rich pickings for designers to create beautifully animated spaces in which to locate their stories and games. For example, the atmospheric, swampy bayou featured in Red Dead Redemption 2.

A scene from the immersive watery world of Red Dead Redemption 2.

A scene from the immersive watery world of Red Dead Redemption 2.

Or the wild, watery, and untamed imaginary worlds of estuaries and inland marshes depicted in Assassins Creed: Valhalla - which also bear an uncanny resemblance to the Severn Estuary, home to WWT Slimbridge.

As Harley Todd, WWT’s Content Creator and keen gamer explains, it’s the mysterious or sometimes otherworldly feel to these wetlands, like those in Horizon Forbidden West, that makes people want to escape to them.

‘It’s the sense of the unknown and exploration that I’m drawn to. Even the darker more malevolent atmosphere of say monster filled swamps can be fun to explore – both thrilling and terrifying at the same time.’

Gamers can dive beneath the surface of the visually stunning wetlands in Horizon Forbidden West.

And while the first Avatar film drew inspiration from the beauty of our rainforests and their creatures, it’s the magically re-imagined wetlands of twisted mangroves, colourful corals, turquoise lagoons and swaying kelp forests that are the stars of the sequel, The Way of Water. The vibrant bioluminescence and beauty of Pandora’s aquatic landscape, all pay homage to the real-life wonders of the watery worlds found on our coastal margins.

Wetland paintings to evoke wonder and celebration

For some artists though, it’s not enough to just capture the unique beauty and quality of these places. It’s also about using art to evoke a sense of wonder in others and inspire them to love, cherish and celebrate these wonderful spaces.

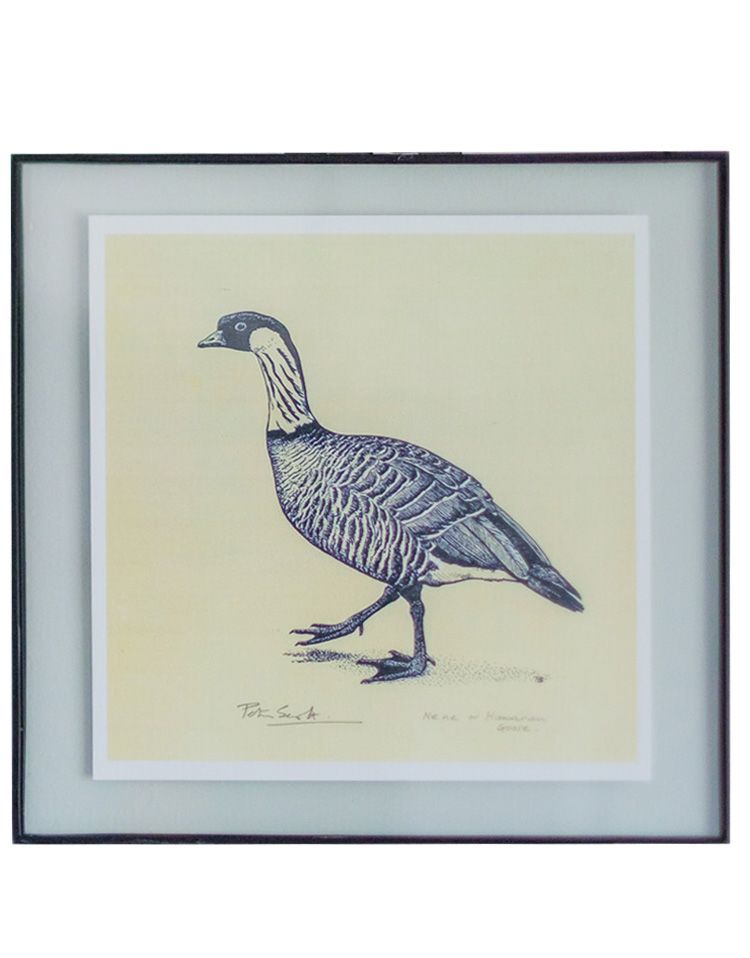

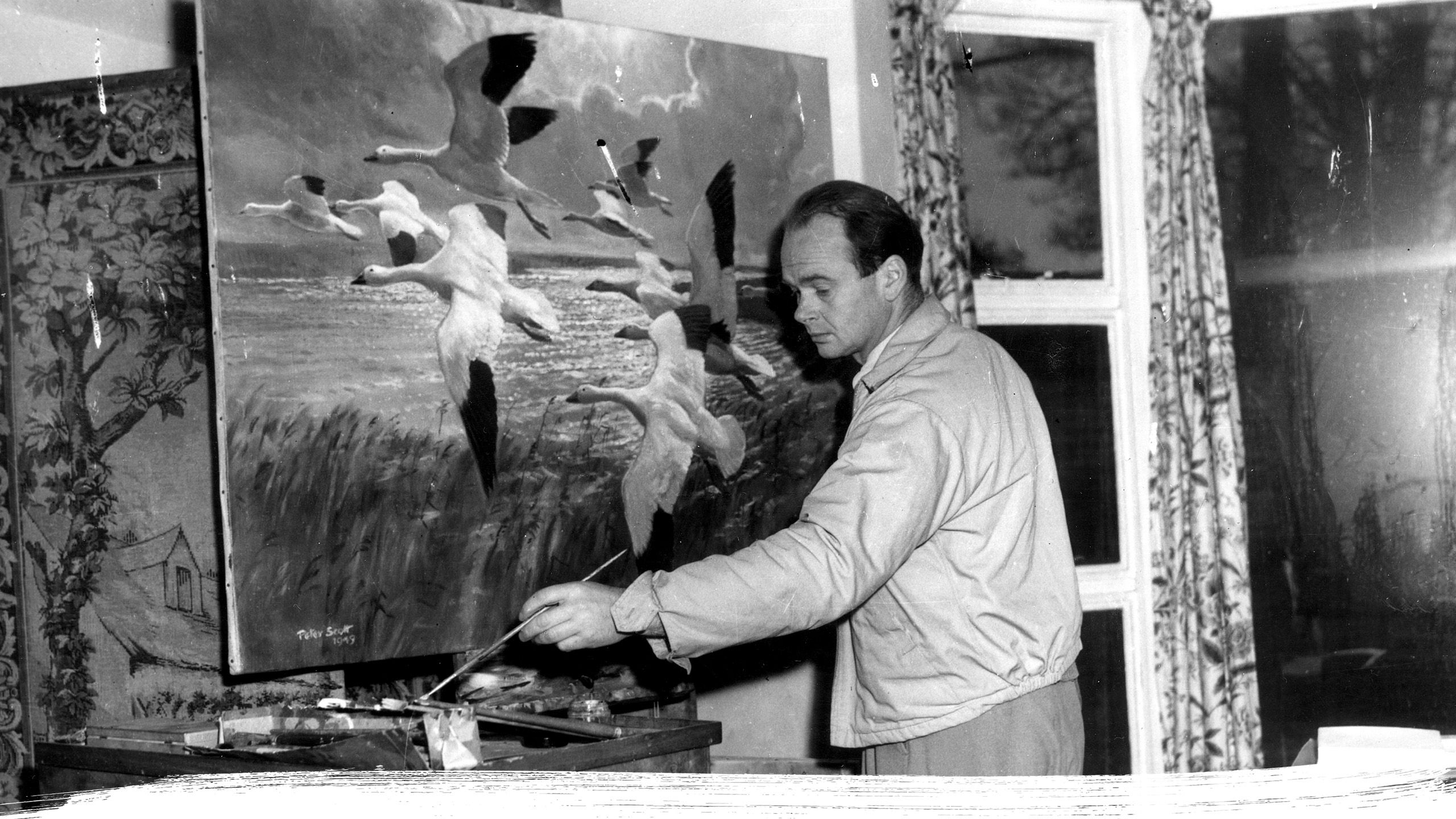

Sir Peter Scott’s paintings are famed for their ability to capture the power and mystery of his beloved birds, as they fly in huge skeins, set against the wild landscape of clouds, sunsets, mudflats and marshes.

For WWT’s founder, art was a constant. Hardly a day would go by without Scott picking up a pencil or a brush. At meetings he would doodle on his papers, producing drawing after drawing of heads of geese, ducks and birds in flight.

But as Scott's wife Philippa writes in the Art of Peter Scott, Images from a Lifetime, the desire to share his enjoyment of wetland nature with others was also a key motivation behind his painting.

‘By putting on canvas things he had seen while out in the marshes at dawn or sunset, he was trying to bring something of the beauty and excitement he had experienced for others to enjoy.’

‘The first of my objectives is to give pleasure to people, as many people as possible, some possibly not yet born. I like to draw things that have excited me, to reflect my own enthusiasm for nature in general and especially for birds. I like to help to educate others to enjoy then, thereby enriching their lives too, and at the same time advancing the cause of conservation.’

Sir Peter Scott

Sir Peter didn’t just restrict his art to big canvases, as Chris Moore, author of a new biography, Peter Scott and the Birth of Modern Conservation, explains:

‘He also created designs for pottery and cigarette cards, all adorned with his beloved birds. By working in this way he was able to bring wetlands and their wildlife to the masses, something that was very important to him.’

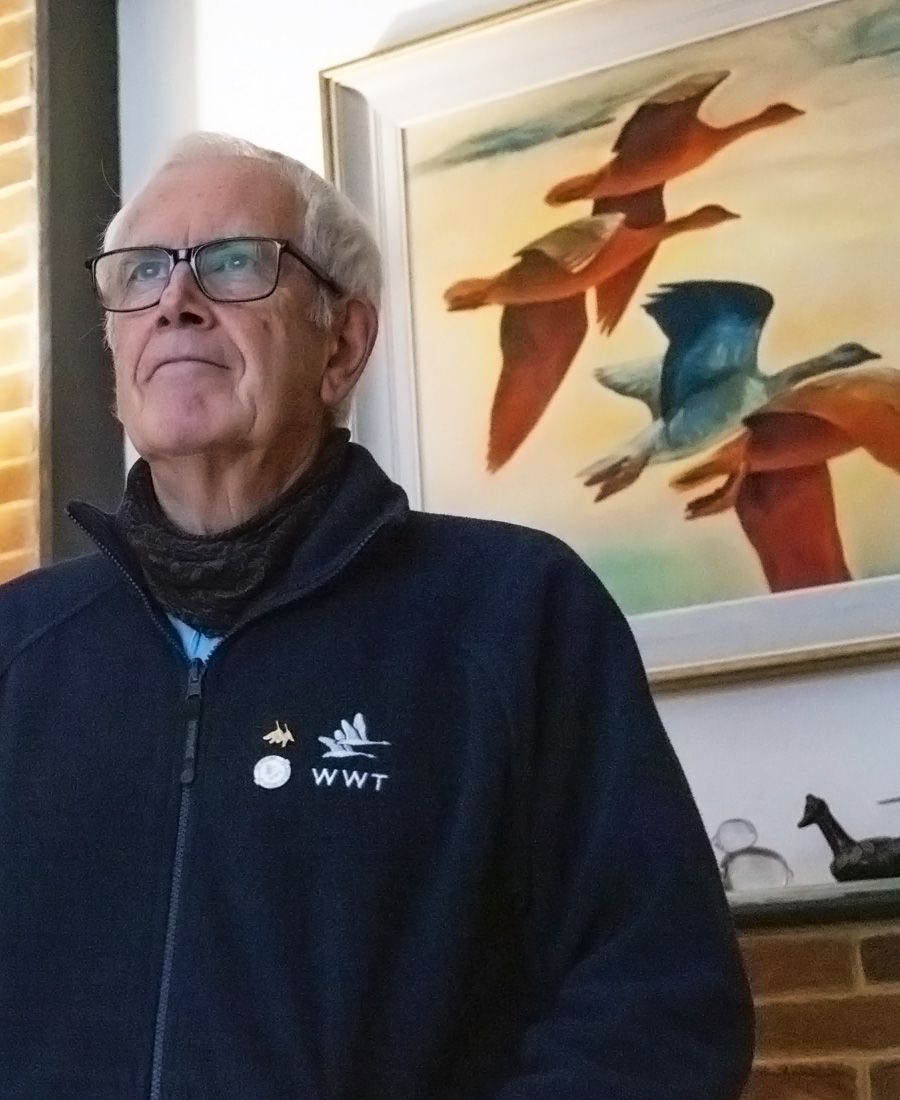

And for Chris Moore, his admiration of Scott’s art lies not just in its ability to capture a moment in time, like the skein of geese frozen perfectly in flight. It's also the power of his paintings to create an emotional connection in the viewer with these wild places.

‘In essence, they evoke memories of some of the fantastic birds I have seen over the years and the lovely places I have been to see them, with a promise of more great experiences to come!’

Chris Moore

Chris Moore in Sir Peter Scott's study at Slimbridge

Chris Moore in Sir Peter Scott's study at Slimbridge

Drawn to water

This connection between art and nature is something that’s woven into our DNA at WWT and continues to inform the way we create amazing nature experiences for our visitors to enjoy at our sites.

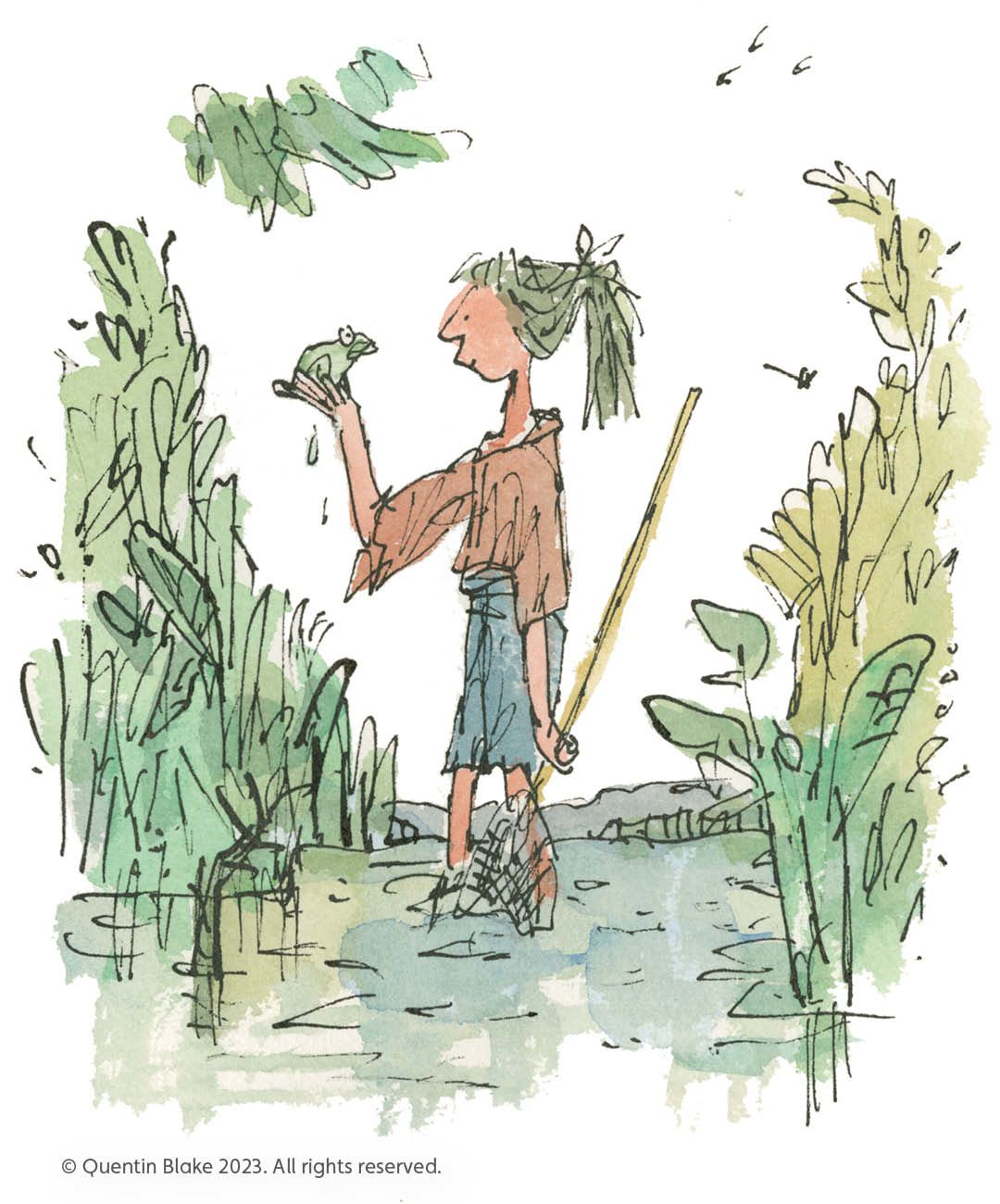

Drawn to Water is a year-long collaboration between WWT and renowned illustrator Sir Quentin Blake that seeks to use the artist’s work to explore the wonder of wetlands. Through a touring exhibition of Quentin’s work, featuring previously unpublished pictures, as well as seasonal trails beautifully illustrated with Quentin’s images, visitors to WWT’s wetland centres will be taken on a journey of discovery that explores the seasonal highlights of our sites and encourages them to think how nature, particularly wetland wildlife, is represented through art.

'I am delighted to be sharing my pictures with WWT sites and their visitors through the Drawn to Water experience. This project appealed to me because I have a lifelong fascination of drawing wetland wildlife, especially birds.'

Creating an emotional connection with nature.

The arts have the power to do so much more than just inspire us. By inviting a deeper connection with our wild places, they can also encourage a greater understanding for what they are and why we need to cherish them.

For singer songwriter David Gray, nature imagery runs deep throughout his work. But there’s one song, in particular – Arc – that’s rooted in one of the most memorable and widely loved sounds of our wetlands, the haunting call of the curlew.

‘It’s a call that fills a landscape, that resonates in the fibre of our being that goes beyond language. It’s a visceral, other worldly sound. When you hear it, it’s as if it’s the sound of these lands and you’re being reconnected to something old. There’s a sense of deep ancestral connection. It’s an incredible call, iconic, powerful. And there’s a magic there that we can’t afford to lose. It was that sound that inspired me to write a song.’

Credit: Bart Gras/Xento Canto

Just as it was for Scott and his paintings, for Gray, his songs are a way of sharing his love of nature with people who otherwise might not have the opportunity to connect with the wonder of the natural world.

‘People in cities, especially in deprived areas, have less access to the magic and healing power of nature. Art, words and music all have the ability to lift people out of the grind of their everyday lives and encourage them to celebrate this connection with nature that we all have, but maybe some of us have lost.’

For Gray, this ability to move people is the power of words and music.

‘In simple ways, I hope I can make a lasting difference by connecting people, by creating a song that can be a monument to nature, that shows us how to celebrate this bird.’

The power of a story

Oscar winning actor, playwright and WWT Ambassador, Sir Mark Rylance discovered an enduring love of wetlands during lockdown. He now regularly visits London Wetland Centre where he goes to find peace and inspiration.

‘I like those in-between places, where the birds move between land and water. For me that’s where the creativity comes. Those places of confusion. Mysterious, irrational, unconscious places of water.’

In 2021 Rylance took on the starring role in a Radio 4 drama about wetlands, called the Song of the Reed. It follows the survival of a fictional nature reserve in Norfolk and shows the contribution wetlands can make towards fighting the climate crisis. According to Stanford University stories are remembered up to twenty two times more than facts alone. And for Rylance, it’s this ability of the arts to tell stories about nature that appeal to our hearts as well as our minds, that makes them so crucial in helping solve the climate crisis.

It’s this emotional connection that stories can achieve that Rylance believes is so critical if people are to be inspired to tackle the effects of climate change. Afterall, who can fail to be moved by Rylance’s reading of this love poem to the swan.

‘We really need the arts to remind us how we are part of the same family as the nature around us. I feel like we’ve got to fall in love with nature again; we do incredible things for each other when we fall in love.’

Art to imagine a better world

Sir Peter Scott’s final painting still stands on the easel in his studio at WWT Slimbridge. Unfinished at the time of his death, it’s a testament to the power of art to imagine a better future and in imagining it, help make it a reality.

In 1989 Scott had been working on a proposal for a new wetland centre in London. This painting was created to show what it would look like and shows wigeon flying in over a stretch of open water.

Image credit: Rupert Marlow Photography

Image credit: Rupert Marlow Photography

At the time of its painting, there were no wigeon on the redundant reservoirs. But ten years later, after they were converted into a wildlife haven and London Wetland Centre opened, wigeon had become a regular visitor. It’s testament to the power of the imaginative arts to help show us the shape of how things could be.

Stepping into a saltmarsh

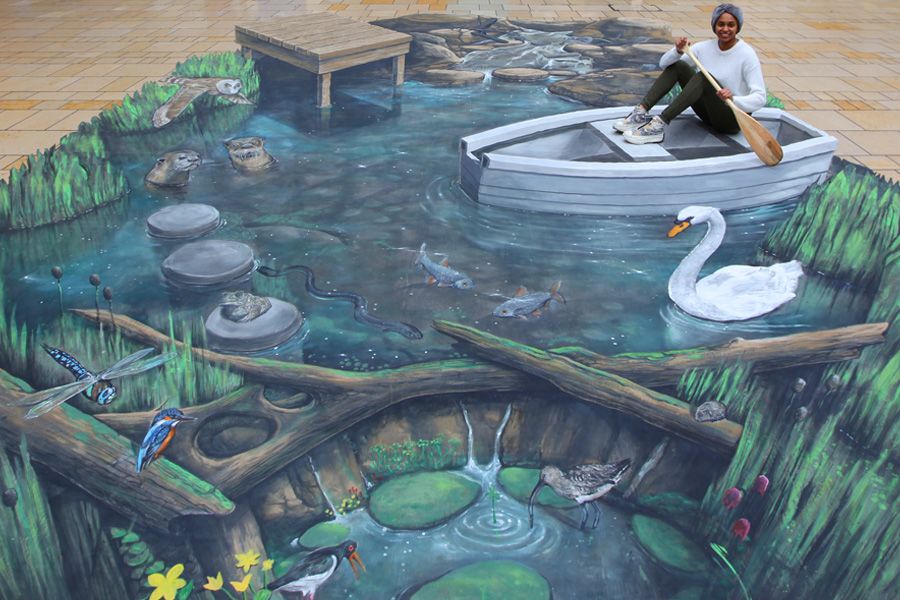

For World Wetlands Day 2023 we took this a step further by commissioning an interactive piece of 3D art where people could literally step into an imagined wetland. Viewers were able to experience what a nature filled future could actually look like by sitting in a boat, standing on a jetty and snapping a photo as they planted a shoot in the saltmarsh.

The piece demonstrates the amazing potential for wetland revival and creation. It features iconic wetland species like curlews and kingfishers, otters and dragonflies, and was rolled out at a shopping centre in Bristol before touring round the UK.

Dreamers of the future

At the climate COP in Egypt, thousands of artists gathered to add their voices to the political negotiations. Evidence that while scientists can inform discussions around climate change, the fight to protect our planet and its biodiversity needs all kinds of voices on the front line, including from the arts. As sustainability expert and leading advocate for climate optimism, Solitaire Townsend, explains, artists are the dreamers of the future.

‘Overflowing with energy, new ideas and commitment to tell new stories, arguably the success of Culture at COP tells us something about what’s missing from the desperately important, but somehow not compelling enough, political work to save our climate.’

Just as Sir Peter Scott’s imagined wetlands helped make his dream of London Wetland Centre a reality, Culture at COP showed the potential of the arts to change our climate future. How by fuelling our imaginations, the arts can help realise and drive action towards an alternate world not dependent upon fossil fuels and the exploitation of nature.

Art and activism

Artists have long used their talents to draw attention to the social and political issues of the moment.

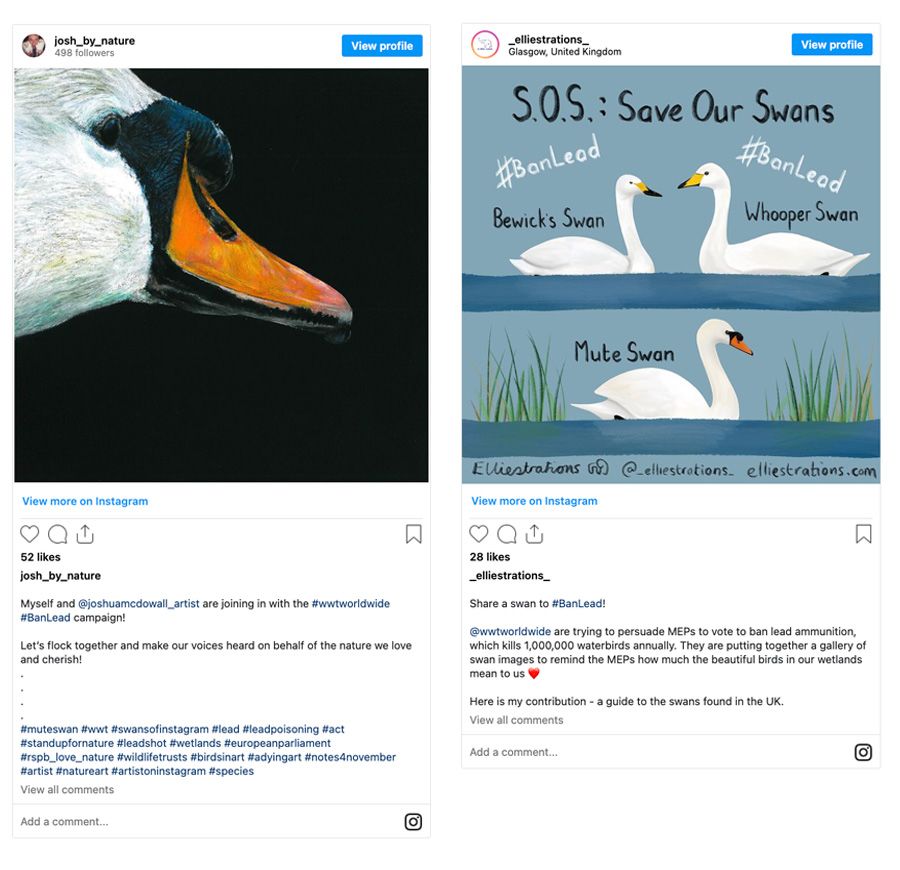

In November 2020 the EU was considering a vote on banning the use of lead shot in EU wetlands. This was the culmination of twenty years of research, lobbying and hard graft by WWT and our partners. As the vote approached, WWT launched a callout to supporters to ‘share a swan’ picture as a symbol of hope that decision-makers would place the health of our environment first. The response was phenomenal and provided a crucial rallying cry that helped tip the vote in favour of the ban.

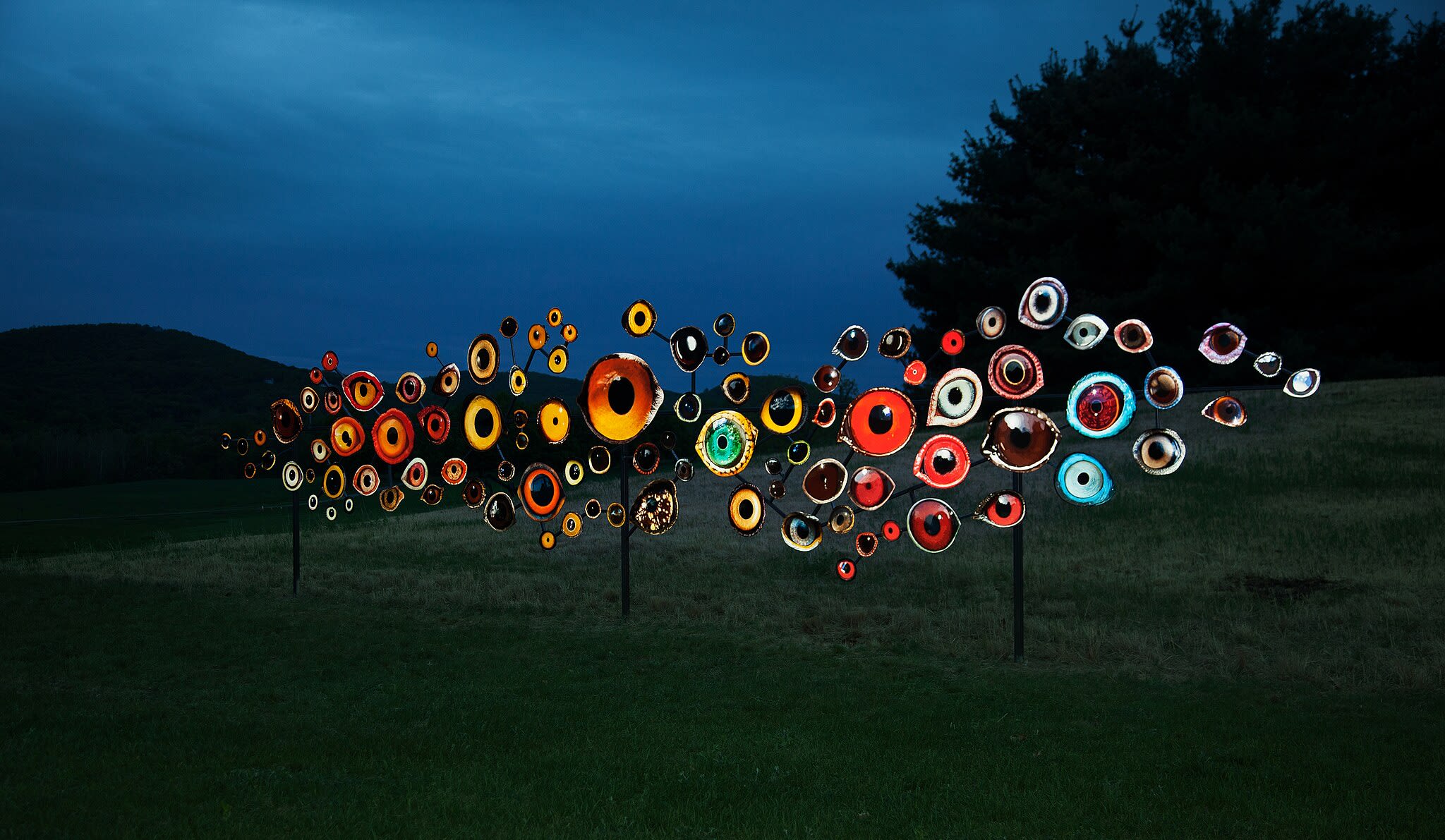

Today creative minds around the world are rallying around the issue of climate change. Artists like Ai Weiwei, with his giant tree roots cast in iron and Jenny Kendler with her Birds Watching that features the eyes of 100 bird species threatened or endangered by climate change, challenge us to wake up, open our eyes and see what’s around us in a new light.

Jenny Kendler’s Birds Watching at the Eden Project in Cornwall. Source, Wikimedia Commons

Jenny Kendler’s Birds Watching at the Eden Project in Cornwall. Source, Wikimedia Commons

And that's definitely something achieved by Artist Lorenzo Quinn with his arresting sculpture, Support. Created for the 2017 Biennale in Venice, it depicts a pair of gigantic hands rising from the Canal Grande to support the sides of the Ca’ Sagredo Hotel.

Support: monumental hands rise from the water in Venice to highlight climate change.

Support: monumental hands rise from the water in Venice to highlight climate change.

The sculpture makes a powerful visual statement about the impact of climate change and rising sea levels on the historic city. It highlights the fragility of the Venetian building, while the hands holding up the walls remind us of our capability and responsibility to act before it's too late.

‘Venice is a floating art city that has inspired cultures for centuries, but to continue to do so it needs the support of our generation and future ones because it is threatened by climate change.’

Lorenzo Quinn

In this way the arts can provide a potent portrait of what we stand to lose and the dire environmental consequences if we don’t act now.

The arts can play a pivotal role in bridging the gap between ideas and behaviour change for climate change. It can provide a place where creativity and dynamism combine to transform our minds and ways of thinking.

A summoning spell

Throughout time, artists have used wetland nature as muse and inspiration. And in turn, their works of art have allowed people to re-imagine and question their relationship with nature and encouraged them to take action to protect it.

As we seek to find answers to our climate and environmental crises, what’s clear is that if we are to create a sustainable future for ourselves and the planet, we need everyone, from scientists to field conservationists, performers and artists, to grassroots activists and local guardians to play their part.

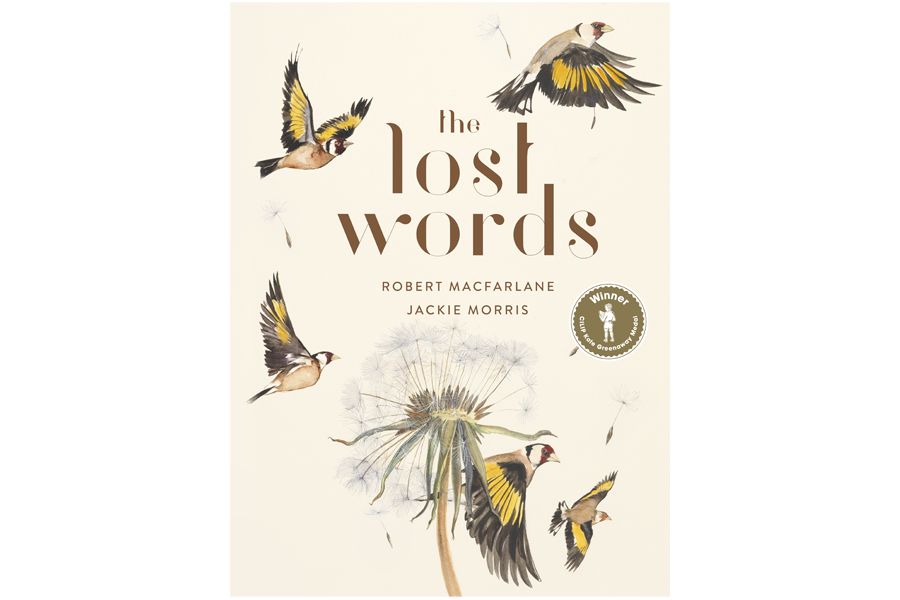

When acclaimed British writer Robert Macfarlane teamed up with artist Jackie Morris to create The Lost Words: A Spell Book in 2017, few could have imaged the cultural phenomenon it went on to become. The book was created in response to the removal from a widely used children’s dictionary of everyday nature words, from kingfisher to otter, bluebell to heron, and their replacement with tech words, including broadband and chatroom.

‘It seemed to me that the disappearance of a common language of nearby nature from the lives, stories, songs and conversations of children – no from all of us – was something to be resisted.’

Robert Macfarlane

For each lost word, a summoning spell was written to be read aloud. And as the book’s popularity spread, it seemed that something about its origin-story and the bigger crisis of our relationship with nature, caused people to quickly take it to their hearts.

Extracted from The Lost Words by Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris.

Extracted from The Lost Words by Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris.

MacFarlane started to receive photos and films of the spells being chanted, performed and spoken out loud. Grassroots campaigns sprang up to raise money to place copies in primary schools throughout the country. It has since gone on to be adapted for dance, outdoor theatre and classical music around the world.

So perhaps it’s fitting our final words should go to the book’s author, Robert Macfarlane, written on the fifth anniversary of its publication.

‘Perhaps the whole wild caboodle of the story so far says something about how art can still move politically and generatively through culture and how utterly vital the living world is to all of us here, now for well-being in the profoundest sense.’

Delve deeper into wetlands

Inspired by Monet's ponds? Find out how to create your own mini-wetland wildlife haven.

From ponds to lakes, estuaries to rivers, discover more about our wonderful wetland habitats.