Pollution busting wetlands

The planet’s biodiversity is in free fall. Could wetlands be the answer?

The world’s wetlands are increasingly at risk from pollution, threatening drinking water supplies and food production for millions and risking a catastrophic loss of biodiversity.

Wetlands, however, could provide a solution to these problems and help turn the tide on the environmental crises we face.

These are the questions that weigh on David Revill’s mind as he watches sewage being discharged every day into his beloved River Wye. David runs a salmon beat on the lower reaches of the river and for ten years he’s watched in horror as the river and its wildlife have deteriorated.

David Revill on the River Wye

David Revill on the River Wye

‘When I first moved here the River Wye was one of the premier salmon rivers in the UK, with a reputation for having some of the biggest fish. It was idyllic, beautiful and diverse and provided the perfect home for water voles, otters and kingfishers. But in the last six years I’ve seen its once crystal-clear waters turn green and brown. There’s been a dramatic drop in the amount of wildlife. Our salmon catches have gone down by nearly 75% over the past five years. It’s becoming a silent river.’

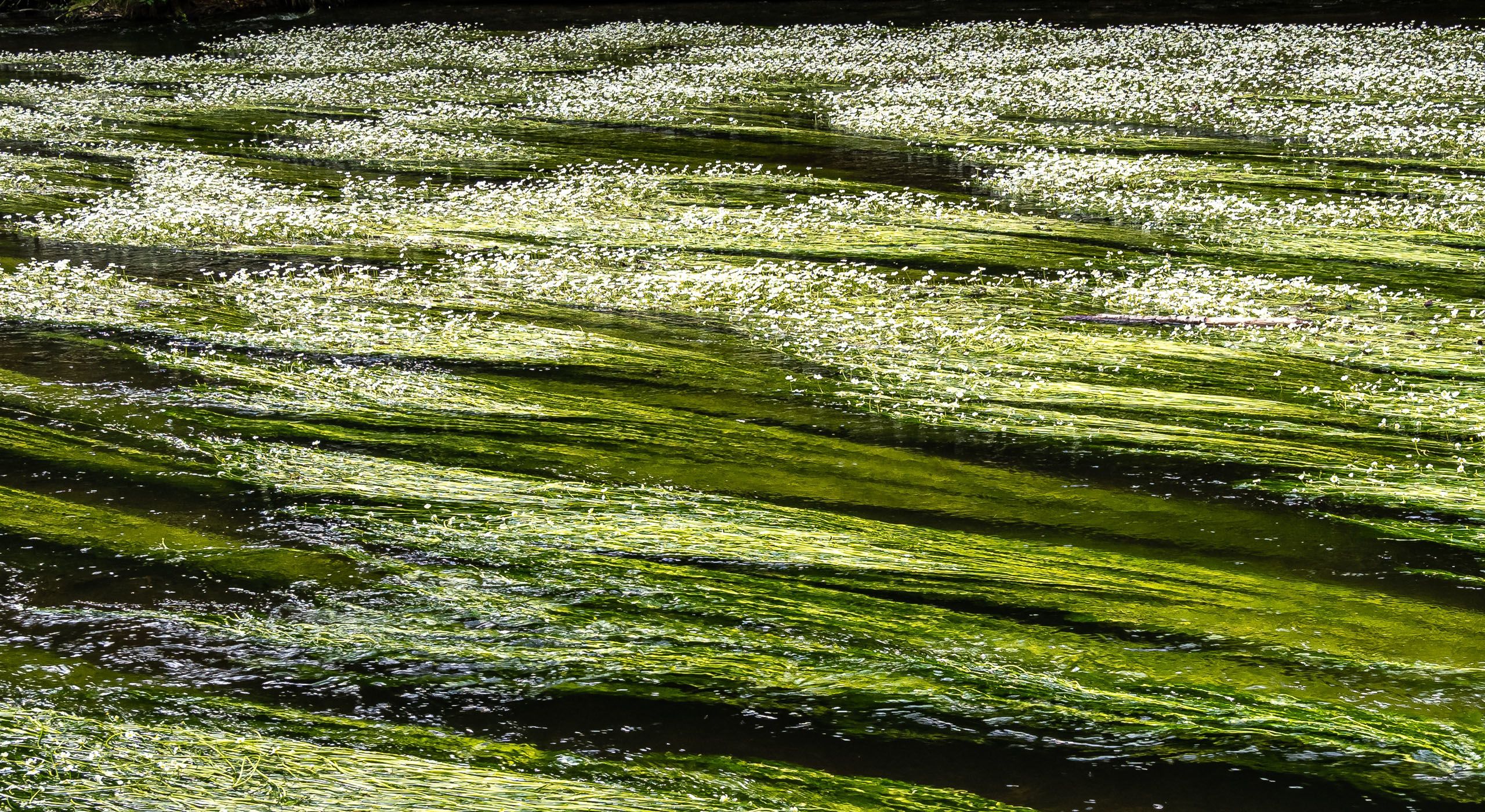

The River Wye is an essential migration route and key breeding area for many nationally important wetland species, including otter, salmon and twaite shad. It is covered by numerous conservation laws. But it’s facing ecological collapse. The Wye’s once vast carpets of water crowfoot, which shelter essential fish nurseries and which are full of filter feeders such as black fly larvae, are disappearing, suffocated by algae blooms.

Water crowfoot, one of the most beautiful natural spectacles of an early English summer. It’s a kind of aquatic buttercup.

Water crowfoot, one of the most beautiful natural spectacles of an early English summer. It’s a kind of aquatic buttercup.

And this isn’t an isolated incident. The facts are terrifying. According to the Environment Agency every river in England is now polluted beyond legal limits, with only 14% of good ecological standard. And this is despite the government’s target in its 25 Year Environment Plan for 75% of water bodies in England to be in a good condition ‘as soon as possible’.

For people like David, who live and work alongside our rivers every day, these figures come as no surprise. But during lockdown many more of us turned to our rivers and coasts for relief and escape, and took up new hobbies such as paddle boarding or wild swimming.

As these once fringe activities became more popular they heightened interest in and concern for the quality of waterways and wetlands. And, as MPs debated the problem of water companies routinely dumping huge amounts of raw sewage into our waterways each year, campaigners and water users took to social media to share images and stories of raw human sewage pouring into our rivers and seas.

What some had been shouting about from the sidelines for years had become the subject of mainstream concern.

What’s causing the problem?

As our rivers become more polluted so do our wetlands. Wetlands act like sponges, absorbing run-off and floodwater from our watercourses. They are often found in the lower reaches and are fed by numerous streams and waterways. The more polluted the water, the more polluted the wetland. This pollution can build up and have a massive impact on the health of a wetland and its wildlife.

While plastic pollution may be easy to spot, it's the hidden, more difficult to detect pollutants, that are causing the most damage. They include untreated sewage released by water companies, excessive use of fertilisers and pesticides in agriculture, and run-off from roads and towns. All are major contributors to the high levels of pollution found in our rivers and lakes.

The repercussions for people and nature of this ‘chemical cocktail’ of untreated sewage and agricultural and urban pollution is a story that is being played out across the world, nowhere more so than in one of the world’s most beautiful and wildlife-rich wetlands.

Lake Nakuru’s flamingos

The Rift Valley hosts one of the world’s greatest wildlife spectacles. Lake Nakuru is the jewel in Kenya’s wildlife crown, its shimmering turquoise waters providing one of the world’s most important foraging sites for lesser flamingo.

They gather on its shores, forming vast pink clouds, to feed on the blue-green algae that live there. The lake is also a major nesting and breeding ground for up to 400 other bird species, yet this UNESCO World Heritage Site is under threat; Nakuru used to be known as ‘Flamingo Town’, but not anymore.

It’s estimated that millions of litres of toxic water are emptied into the lake every day.

This cocktail of run-off from farmland and untreated sewage from rapidly growing townships nearby, combined with the overuse of water for irrigation, is changing the quality of the lake’s water, with devastating impacts on the wildlife and the thousands of people who rely on it for their livelihoods.

There are fears that the flocks of flamingos that made Lake Nakuru such a popular tourist destination are disappearing, with thousands migrating to other less spoilt areas.

The sewage problem

Across the world, from Kenya to the United Kingdom, pollution from untreated sewage has become a huge problem.

A horrifying 80% of global wastewater enters our waterways without adequate treatment, with devastating consequences for wildlife and people.

It’s estimated that in England, raw sewage discharged by water companies directly into rivers accounts for 36% of damage. Wild swimmer Lindsey Cole experienced the horrors first-hand as she swam the River Avon dressed as a mermaid to raise awareness of the issue.

Lindsey Cole, environmental campaigner and human mermaid

Lindsey Cole, environmental campaigner and human mermaid

‘About four days in I got sick and was violently ill for 24 hours. I had to get out and rest in the support canoe. There was really heavy rain and it was then that I saw stinking dirty water gushing out of pipes straight into the river.’

The chicken problem

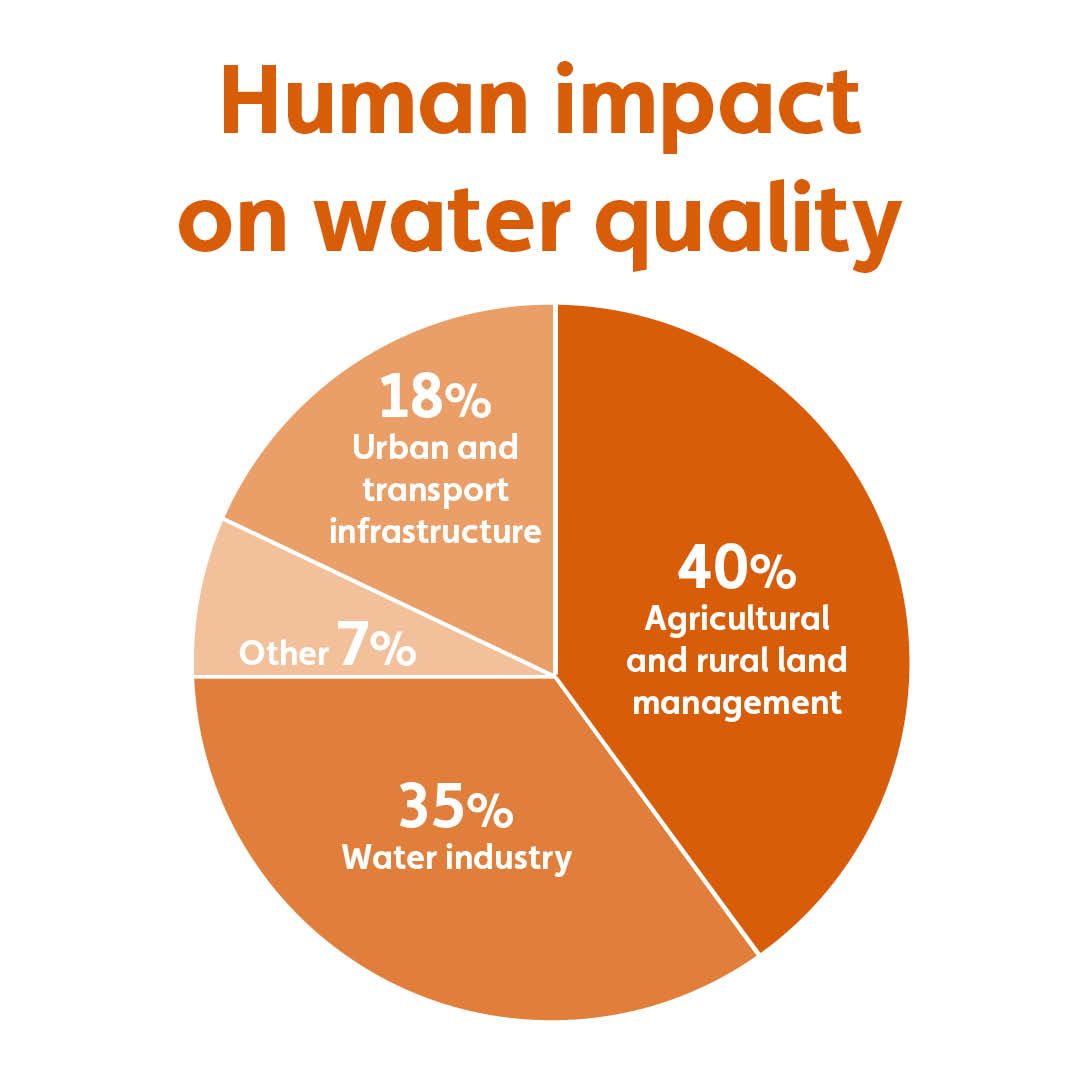

But while sewage dominates stories of river pollution in the UK, it’s not the major cause. In England, run-off from agricultural industries is responsible for 40% of the damage, particularly in rural areas, something that David Revill is only too aware of when it comes to his beloved River Wye.

‘You want to know the cause of this great river’s demise? Chickens. Or 20 million of them to be exact.’

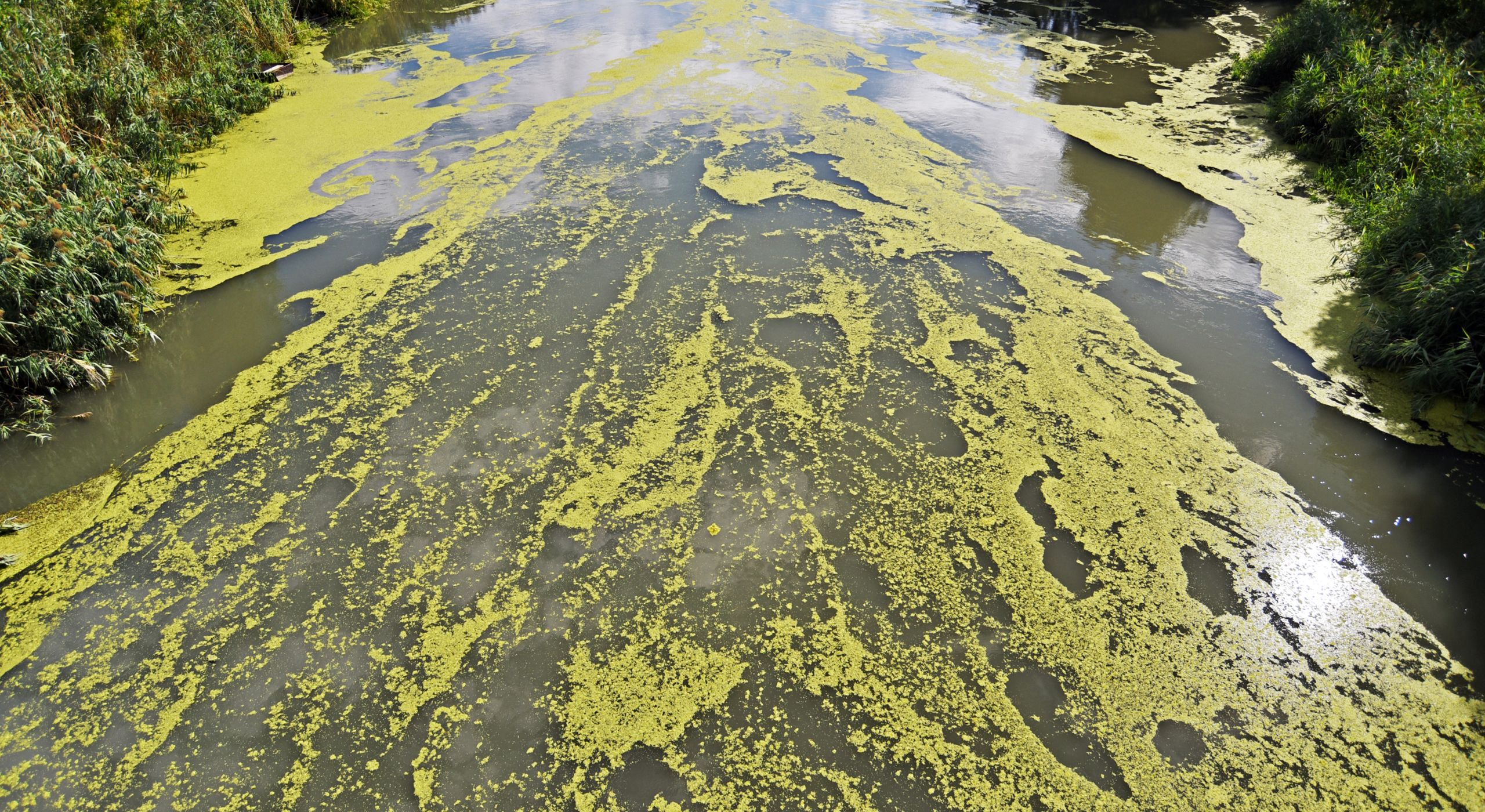

The River Wye has become the industrial chicken farming capital of the UK, with factories containing tens of thousands of chickens found across the catchment. And it’s the chicken dung that’s routinely spread on the land as manure, that’s widely acknowledged to be the cause of the problem. It’s high in phosphates and nitrates and when it rains, these nutrient rich pollutants get washed and leached out into our rivers. It’s this excess of nutrients that’s damaging our waterways and causing plagues of algae blooms.

The challenges faced by our wetlands and waterways are only set to get worse.

Climate change will alter river flows, increase concentration of pollutants and increase the growth of algae. Increased water use during droughts and damage caused by flooding, both of which are becoming more frequent due to climate change, are also compounding the problem.

Why are wetlands important?

Clean, healthy wetlands are essential for human health and prosperity. If we pollute our wetlands, we lose so much.

Wetlands are the main source of drinking water for millions of people around the world. If wetlands are polluted, so is our drinking water. Wetlands also provide the water we need to produce food. Without our wetlands we wouldn’t have access to food and drinking water.

Rice grown in wetland paddies is the staple diet of 3.5 billion people.

Rice grown in wetland paddies is the staple diet of 3.5 billion people.

Healthy wetlands sustain the livelihoods of millions in poorer countries.

An estimated half of international tourists seek relaxation in wetland areas.

During the pandemic, more and more of us discovered the wonders of our wetlands and experienced first-hand their restorative powers. Levels of anxiety, stress and depression are increasing but research by WWT is showing that being around blue spaces for as little as ten minutes can help reduce anxiety and stress.

It’s not just people who need clean, healthy wetlands. Some of our most iconic and threatened species, such as otters, water voles, kingfishers and salmon, depend on healthy rivers, ponds, lakes and streams. These wetlands provide homes, nurseries, larders and superhighways for an extraordinary range of wildlife.

Yet the species that depend on these habitats are facing catastrophic population declines. As water quality suffers, so does wetland biodiversity. Without wetlands, wetland wildlife faces a perilous future: one in three freshwater species are now threatened with extinction.

Could wetlands hold the answer?

Without doubt, we’re facing a global environmental crisis in our rivers and waterways – on a massive scale.

As we emerge from the pandemic, and people take stock of what they value most, there are demands for a better world with greater protection for nature. But the challenge remains: how do we go about cleaning up our mess and how do we fund the clean up?

Could nature provide the answer? Wetlands may be the victims of pollution, but because of their unique ability to filter out pollutants they could also be our saviour, and a cost-effective one at that.

How do wetlands work?

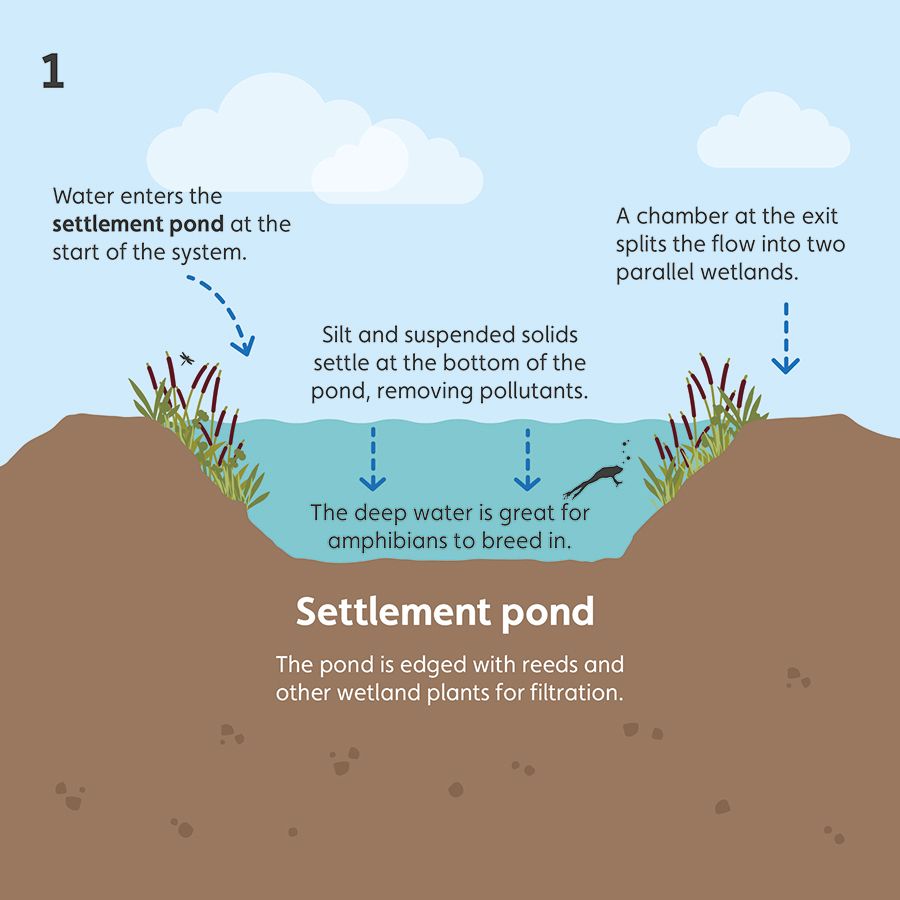

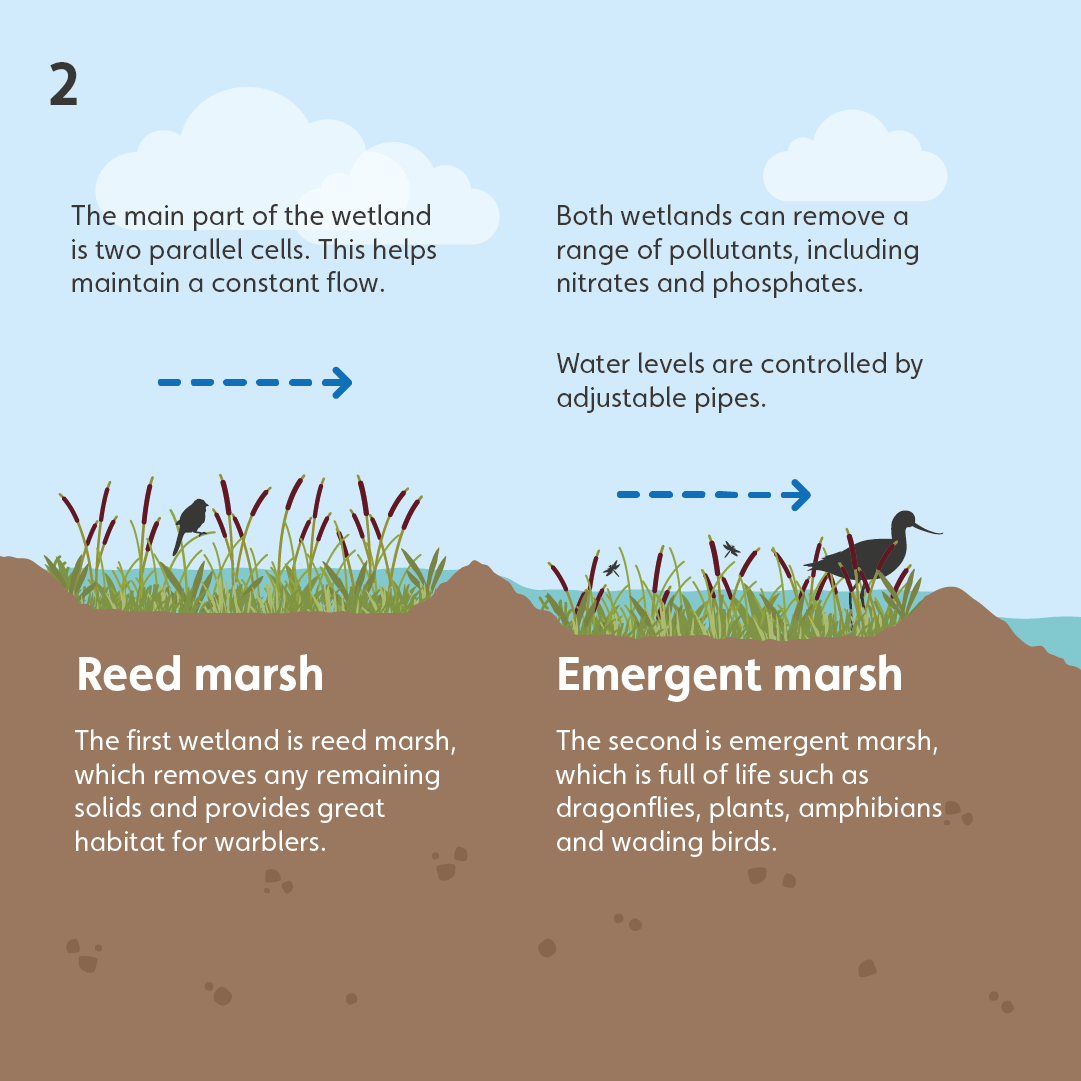

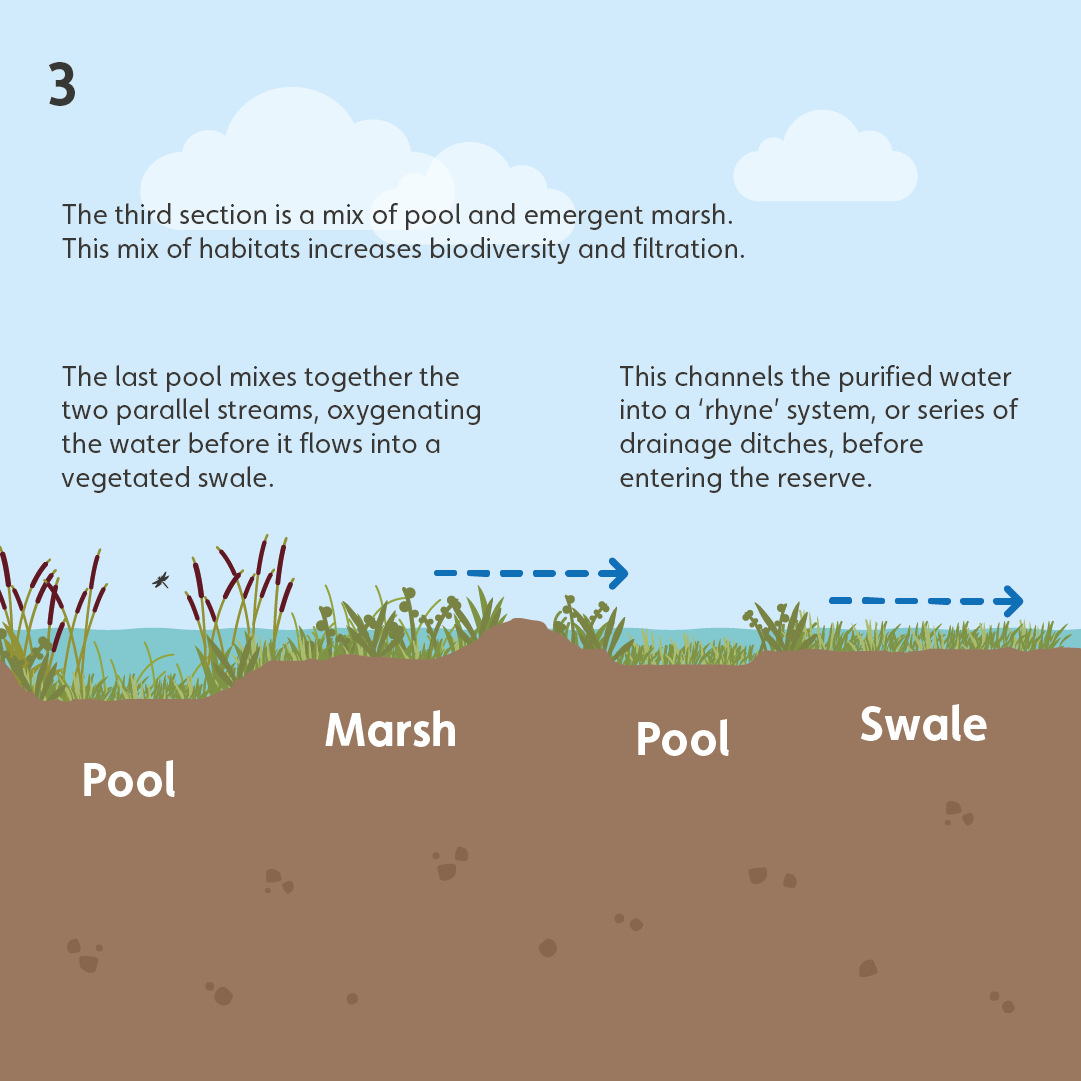

On the banks of the River Severn in Gloucestershire is a series of man-made pools. It might not look anything special, but these wetlands are being put to use by WWT to clean and filter water from nearby cattle barns and livestock. Once purified, the water is allowed back into the wetland reserve without the need for additional treatment.

This treatment wetland at WWT Slimbridge is designed to clean up water from cattle barns and livestock yards.

This treatment wetland at WWT Slimbridge is designed to clean up water from cattle barns and livestock yards.

The system uses pools and native plants to clean the water and has developed wildlife value in its own right, with a total of seven species of dragonfly and damselfly already recorded.

Dragonflies are an excellent bio-indicator (or living indicator) of water health.

Dragonflies are an excellent bio-indicator (or living indicator) of water health.

A new way to treat sewage

Learning from nature and using ‘nature-based solutions’ such as wetlands to tackle the problem of water pollution is an approach that’s gaining traction and one that’s being put to the test by Wessex Water at its sewage works in Cromhall in rural South Gloucestershire. The company has teamed up with WWT to create 12 wetland pools, to prove that nature can be used as a sustainable method of removing excess phosphorus from wastewater.

Instead of using chemicals, these wetlands use natural processes to treat sewage. Credit: Wessex Water

Instead of using chemicals, these wetlands use natural processes to treat sewage. Credit: Wessex Water

‘Until now, the Environment Agency hasn’t really accepted wetlands as a water treatment solution,’ explains Ruth Barden, Director of Environmental Solutions at Wessex Water.

Too much phosphorus in rivers, largely from treated domestic sewage, as well as agricultural and industrial run-off, can lead to excessive algae growth and reduced oxygen levels, upsetting the balance of life in waterways. At present, water companies use a combination of iron-based chemicals and energy-intensive filtration systems to remove phosphorus, which Barden admits is economically and environmentally unsustainable. The plants and microbes at Cromhall wetland absorb the phosphorus naturally.

The wetland has five years to show it can produce water released into the nearby Tortworth Brook with phosphorus levels no higher than 2mg per litre. After just 18 months the average levels are already down to 0.5 to 1mg per litre. But it was when the first swans arrived to set up home on the wetlands that Ruth realised the experiment was bringing even greater benefits:

A visible boost to wildlife.

A visible boost to wildlife.

‘It was an early indication that, as well as filtering out pollution, our wetlands are also helping to boost wildlife.’

And they’re not the only ones enjoying a new home.

Just six months after the wetlands were created, skylarks and linnets – both on the BoCC4 red list of threatened species – were spotted, plus six species of bat and smooth and palmate newts.

It’s this connection between wetland creation and boosting wildlife that’s so important to Tom Hayek, Senior Project Manager for Nature-based Solutions at WWT:

‘We believe that by looking after our wetlands and their wildlife we can help rebuild some of the world’s most valuable ecosystems and halt the catastrophic biodiversity loss.’

It’s not just water companies that can benefit from using wetlands. Finding a sustainable way of disposing of wastewater can present a significant cost saving for businesses too.

A dram good way to reduce pollution

Nestled within the Dumgoyne hills in the Scottish Highlands, just 14 miles north of Glasgow, is the Glengoyne Whisky Distillery, which has teamed up with WWT to use wetlands to treat its wastewater naturally, enabling the company to save money and improve the environment at the same time.

The whisky distillation process creates a waste liquid called ‘spent lees’. This wastewater is now filtered on site instead of having to be sent off site to an industrial treatment plant. The liquid makes its way through a series of 12 specially created pools in which reedbeds filter and clean the liquid before it flows into the local burn and on to Loch Lomond.

‘We are always looking at options for improving our waste management and wetlands seemed like the perfect solution. They allow us to reduce waste, cut down on waste transportation and be more environmentally friendly. What’s more, they attract a huge range of wildlife to the area, which is already renowned for its wild geese.’

In Scots Gaelic, the location of the distillery - Glengoyne – loosely translates to 'The Valley of the Wild Geese'. Credit Paul Marshall

In Scots Gaelic, the location of the distillery - Glengoyne – loosely translates to 'The Valley of the Wild Geese'. Credit Paul Marshall

Using wetlands in this way has enabled the company to cut its overall waste by 25%. The wetlands are excellent for biodiversity, attracting songbirds, dragonflies and other wildlife.

It’s not just on farmland and in rural areas where wetlands can help reduce water pollution.

Turning our cities blue

It’s a sunny spring morning and these school children in North London have swapped their indoor classroom for an outdoor one.

They’re busy getting their hands dirty digging in hundreds of plants to create their own mini-oasis in the heart of their city. They’ve spent the last few weeks designing a wetland for their school garden, and now they’re getting to see their plans become reality.

Their school is one of the ten schools turning to nature to help clean up London’s water. When drains become overwhelmed during heavy rain, water can spill into the sewage system, releasing polluted water into our rivers and even our homes, poisoning wildlife and ruining lives. Climate breakdown and population growth are making the problem worse, as urban drainage systems becomes overloaded.

But these schoolchildren are helping to turn the tide by building mini-wetlands that will help reduce flooding and pollution in their local brook.

‘At the start of the project, 80% of the students, staff and local people didn’t even know the name of their local river. But now the schools have become hubs for reconnecting local people to their stream, the Pymmes Brook.’

How do they work?

The children are creating mini-wetlands – or sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) – that work by capturing rainwater as it lands on the ground or roof. The aim is to clean and slow the flow of water by holding it in a system of ponds, swales and rain gardens.

Much of the rainwater is then taken up by plants, soaks into the ground or evaporates. The rainwater that remains only reaches the drains slowly, if at all, it’s less polluted and there’s no sudden surge of water overloading the system.

The children’s wetlands are also enticing new visitors, including frogs, newts, butterflies and dragonflies, and there’s hope that by creating mini-wetlands such as these in our towns and cities they’ll act as blue or green corridors that help animals move between pockets of nature.

Using pollution-busting wetlands to boost biodiversity

Using wetlands to improve water quality and deal with wastewater is something WWT has been doing for decades. As Tom Hayek explains, in many situations, wetlands can be a cheaper option for helping us deal with pollution.

‘Obviously we’d like to see agriculture and industry clean up their acts. But we’ve been showing for 30 years that natural wetlands can drastically reduce the levels of pollutants that reach our rivers. Treatment wetlands at our centres already deal with effluents from toilets and run-off from our animal collections.’

By demonstrating how water quality can be improved through the use of nature-based solutions, and by partnering with others, WWT is aiming to create a bigger and better network of wetlands to improve water quality and boost biodiversity. Tom Fewins, Head of Policy and Advocacy, explains:

‘The world faces a biodiversity crisis and poor water quality is helping to fuel this. We must urgently turn this situation around and the Government must now adopt wetlands as a powerful weapon in the fight to restore our missing wildlife. We’re calling for a Blue Recovery to create and restore 100,000 wetlands to help address the environmental crisis.’

But the problem of water pollution stretches way beyond our borders. From China to Cambodia, Myanmar to Madagascar, WWT is working to show how wetlands can be used to help tackle the threats that have led to the 84% collapse in freshwater biodiversity.

With a coalition of partners WWT is calling for the implementation of an Emergency Recovery Plan to halt this decades-long decline and restore life to our dying rivers, lakes and wetlands.

‘Our Emergency Recovery Plan presents an outline of straightforward and pragmatic solutions to the freshwater biodiversity crisis that are already proven to work. A strategic approach is vital if we’re to make a global impact.’

And as the lead author of the Emergency Recovery Plan, Dave Tickner of WWF warns, time is running out.

What can I do?

WetlandsCan!

The easiest and best way you can support the fight for better, cleaner, healthier wetlands across the UK is to sign our pledge. Add your voice to the campaign for wetlands today.

Become a member

You can provide ongoing support to protect our wetlands by becoming a member. Your help ensures essential campaigns against water pollution, climate change and biodiversity loss continue.

Gardening for wetlands

You can create your very own pollution-busting wetland at home. This is a great place to start, no matter the size of your garden. Find out how, with WWT’s expert top tips and inspiration.

Learn about wetlands

There’s more to wetlands than you might think. Some of the most threatened habitats in the world, yet also the most vital for wildlife and people, learn more about why wetlands are special.

References

Environment Agency – Catchment planning

Surfers Against Sewage – Water quality report

The Rivers Trust – Why aren't our rivers healthy?

Bioscience – An Emergency Recovery Plan

Water UK – Ten actions for change

RSPCA Assured – We need to talk about chicken

UK Parliament – Water quality in rivers report

Friends of the Upper Wye – Written evidence

Nicola Cutcher – Counting chickens

© WWT images. Shutterstock.