Nature’s super systems

Why wetlands hold the key to saving the

planet’s biodiversity

Our planet faces a biodiversity crisis on a scale never seen before. And nowhere is this more acute than in the world’s rivers, lakes and wetlands.

But looking after our wetland wildlife could help solve the wider problem.

An extraordinary migration starts

It’s a dark and rainy night and one of nature’s greatest migrations is about to begin. It isn’t the familiar epic departure of geese or swans, but the journey of a much more elusive creature. A species so secretive scientists only know it’s on the move thanks to an exciting new research project.

Emma Hutchins, Head of Reserves Management at WWT, explains more:

"Eels live in the wetlands of the Severn Vale until it's time for them to navigate back to their breeding grounds in the North Atlantic Ocean. This fish’s movements were caught by an acoustic camera, which creates images out of sounds, placed at a sluice gate at WWT Slimbridge to monitor their activity"

Footage from the Environment Agency

Footage from the Environment Agency

It’s all part of a conservation project led by WWT, to find out why numbers of eels worldwide have plunged so dramatically. In the past 40 years, the number of glass eels arriving in Europe has fallen by around 95% and the European eel is now listed as Critically Endangered.

What we do know is that industrialisation has created barriers, reduced water quality and altered water levels in our rivers and wetlands, resulting in serious habitat loss and fragmentation. This has coincided with dramatic reductions in numbers of fish species found – not just the eel.

How losing species can affect the whole ecosystem

This decline in eel population has widespread implications. Eels are a significant food source for many wetland animals. The likes of otters, bitterns and herons all like eels because they’re easy to catch and they also have a high fat content. The arrival of millions of young eels or ‘elvers’ in the spring coincides with the breeding season when demand for food is at its height. In short, these extraordinary creatures are vital in maintaining healthy wetlands rich in wildlife.

Rivers, lakes and freshwater wetlands are home to 10% of all species and more described fish species than in all the world’s oceans.

By removing barriers and improving habitat for eels, we can indirectly improve the lives of many other species.

But trying to find out more about the movements of this elusive animal that lives in the dark waters of rivers, lakes and ditches is easier said than done. So conservationists have come up with an ingenious idea – to microchip the eels, similar to how people can microchip pets.

Overnight, Emma and her team have set out nets across Slimbridge’s ponds and waterways. She’s now returned to see what’s turned up in the nets and is attempting to transfer any captured eels by hand into buckets. And with some of the eels measuring as much as 40cm long and as wide as her arm, it’s no easy task.

"It’s a writhing mass of muscular energy, which will erupt out of the bucket if you’re not careful."

Once inserted, the chips will automatically set off a reader placed on a ditch leaving the wetland reserve, letting researchers know when each individual eel has decided to migrate. The microchips can also be read by a hand held reader if the eels are caught in future, enabling researchers to understand how eels are using Slimbridge’s ditches and pools.

In total seven tagged mature female eels were recorded leaving the reserve. As Emma explains, she thinks it’s likely the migration of the mature eels was triggered by high water flows brought on by wet weather and the combination of no moon and cloudy skies creating the perfect cover of darkness:

"Once eels mature in the freshwater wetlands of the Severn Estuary they must be able to swim back to the Sargasso Sea and breed to complete their life cycle - so it’s fantastic to know that the eels can navigate their way back out of our wetlands."

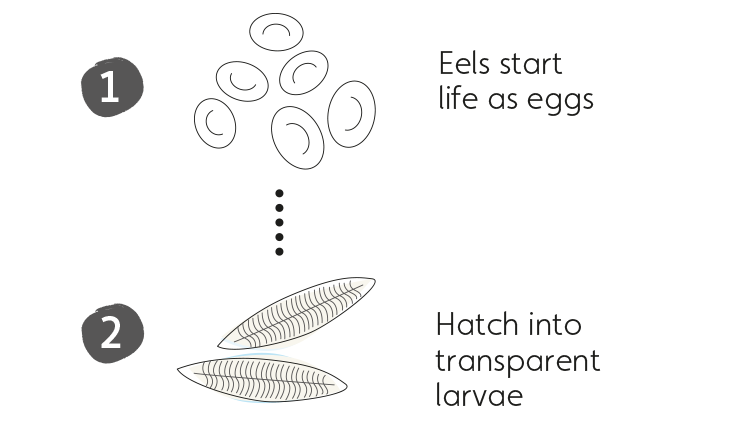

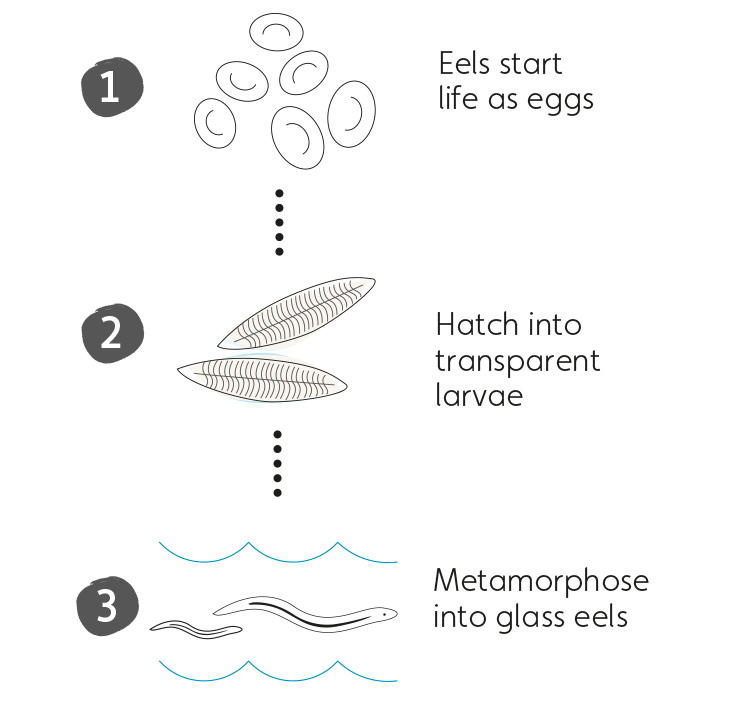

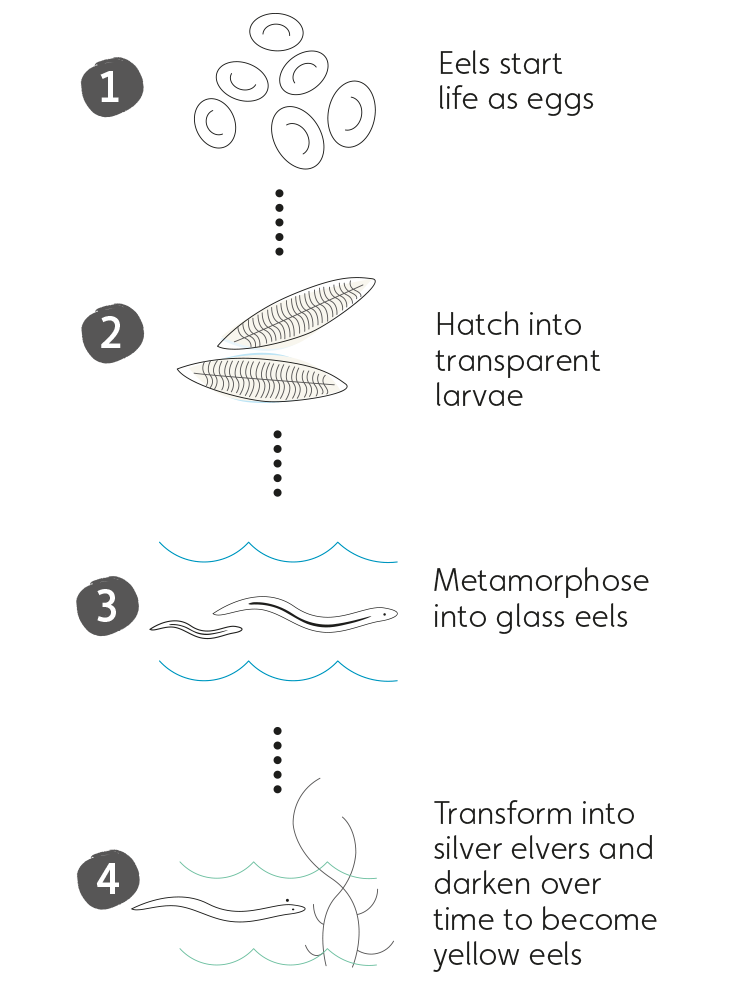

Life cycle of an eel

Eggs hatch into larvae

Eels start life as eggs. The eggs hatch into transparent, leaf-shaped larvae that are swept into the Gulf stream. They drift for up to a few years over a 4,000 mile distance, carried by the currents.

Glass eels

When they reach the shores of Europe and become a certain size, they are triggered to metamorphose into glass eels. At this vulnerable stage they are highly at risk of illegal fishing and predation.

The glass eels use the incoming tides cleverly. They move inland with the rising tide, and bury themselves in the mud as it recedes. This way, they conserve energy and achieve a general inland movement. They do this under the cover of darkness (to hide from predators).

Elvers

Once settled in freshwater, they transform into elvers. Elvers are determined travellers: they head upstream, sometimes even wiggling over wet land to reach unconnected ponds and rivers. However, navigating dams and weirs is near impossible.

Yellow eels

They will steadily darken to yellow eels over the next 10-15 years, and live out the majority of their lives in freshwater habitats.

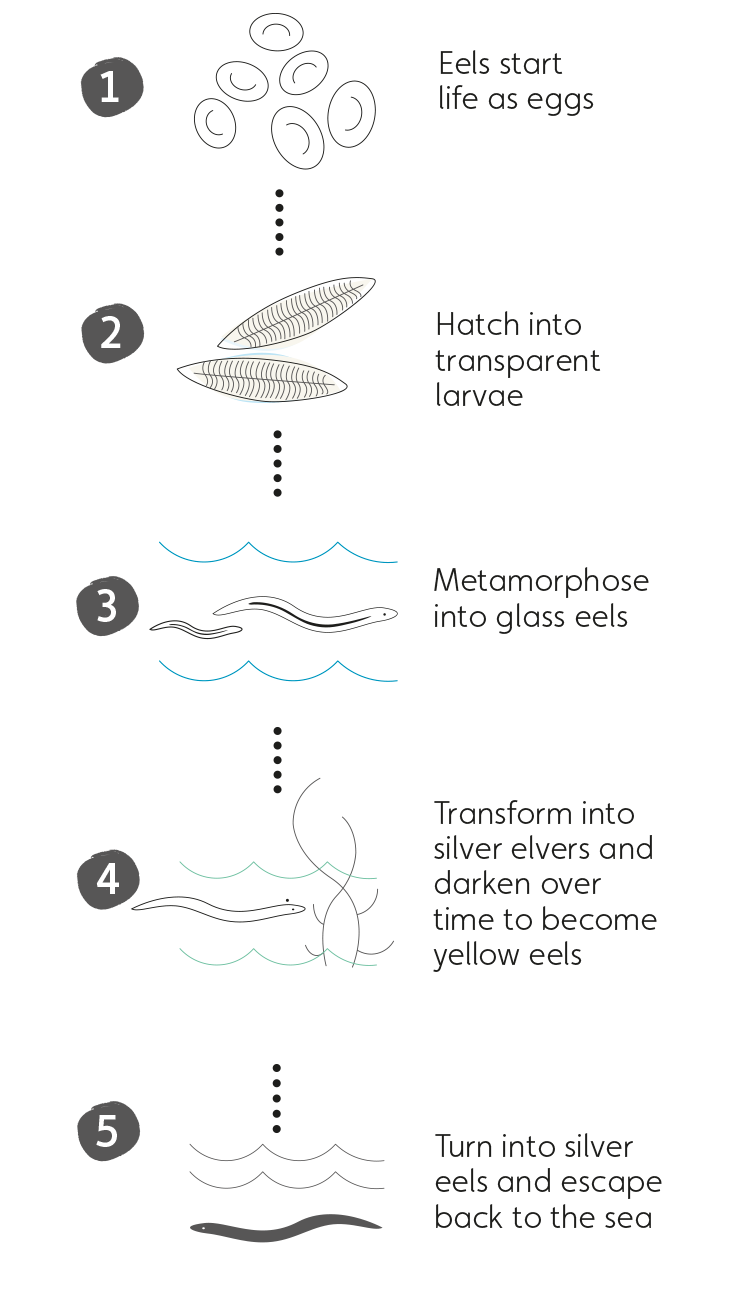

Silver eels

When they’ve reached a certain age, weight and size, this triggers them to turn into silver eels. Their eyes enlarge to cope with ocean gloom, they cease to feed and they alter their body chemistry to cope with salt water. Then they head back to the sea for one final journey. And the process begins again.

No one has ever seen Anguilla anguilla spawning, so for eel biologists, solving this mystery would be the motherlode of all discoveries. But knowing where the eels are going is only part of the challenge facing Emma and her team.

"The puzzle of Slimbridge’s missing eels remains unsolved. We’re confused. We know the young glass eels were coming to Slimbridge twenty or thirty years ago, but for some reason very few are making it now.”

Blocked at every turn

The severe drop in eel numbers is due in part to the loss of wetland habitats, and illegal fishing. But they’ve also been affected by the destructive impacts of man-made barricades that halt their journeys, and hydropower turbines that chop them to pieces.

Slimbridge is on the banks of the Severn Estuary, where some of the biggest tides in the world sweep glass eels miles inland. So the second part of the project that Emma and her team are working on is to make sure routes into the wetland reserve from the Estuary are as eel-friendly as possible. One access point is a 400-metre tunnel built in Victorian times.

"Glass eels should be able to wriggle all the way along and into the reserve’ says Emma, ‘but at very low tides, they face a vertical two-metre climb into the tunnel. The solution? An eel pass which looks like an elongated LEGO brick that helps tiny eels to creep up, effectively a ladder for eels."

Why connecting up our wetlands is good for biodiversity

It’s not just eels that are benefitting from this greater connectivity.

The Severn is one of the most important rivers in Britain for many other species of migratory fish that travel up the Severn Estuary to freshwater habitats to spawn, unlike the eel which travels out to sea.

But research shows that man-made barriers stop large numbers reaching wetlands and tributaries upstream in the Severn Vale.

What is a waterscape, and why do we need them?

Making better connections between wetland reserves like those owned by WWT, and their wider ‘waterscapes’ in the countryside beyond their boundaries, helps the wildlife that lives there and improves biodiversity across the area and beyond. In recent years, the conservation movement has begun to embrace this bigger picture that strives to protect not just nature reserves, not just habitats, but whole landscapes, as WWT’s Head of UK Programmes, Rob Shore explains.

"Recognising this connectedness through the seasons and habitats that is fundamental to so many wildlife cycles, is vital if we want to improve biodiversity."

Protecting one of the UK’s great natural wonders

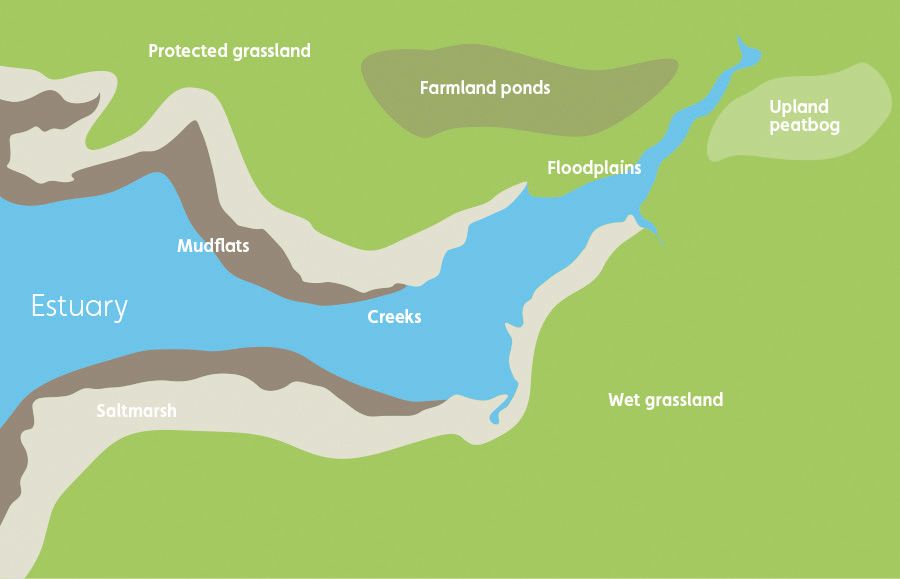

When you think of areas of wetlands teeming with wildlife you might imagine the Amazon rainforest or Bangladesh’s Sundarban mangroves, but some of the best are right on our doorstep. As Rob explains, the Severn Estuary is one of the UK’s great natural wonders and a globally important site for nature:

"From the mighty estuary and the saltmarshes, mudflats and floodplains that border it, to the wet grassland meadows and farmland ponds, the Severn Estuary and the rivers that feed into it create an extraordinary mosaic of habitats. Sir Peter Scott called it the Serengeti of the UK and it is a fantastic showcase for the wonderful diversity of wetlands and the sheer amount of wildlife they can support.

WWT is working with its conservation partners to develop a bold and ambitious plan for this landscape. One that aims to protect and enhance biodiversity, landscapes and ecosystem as a whole."

Bringing a ghost back to life

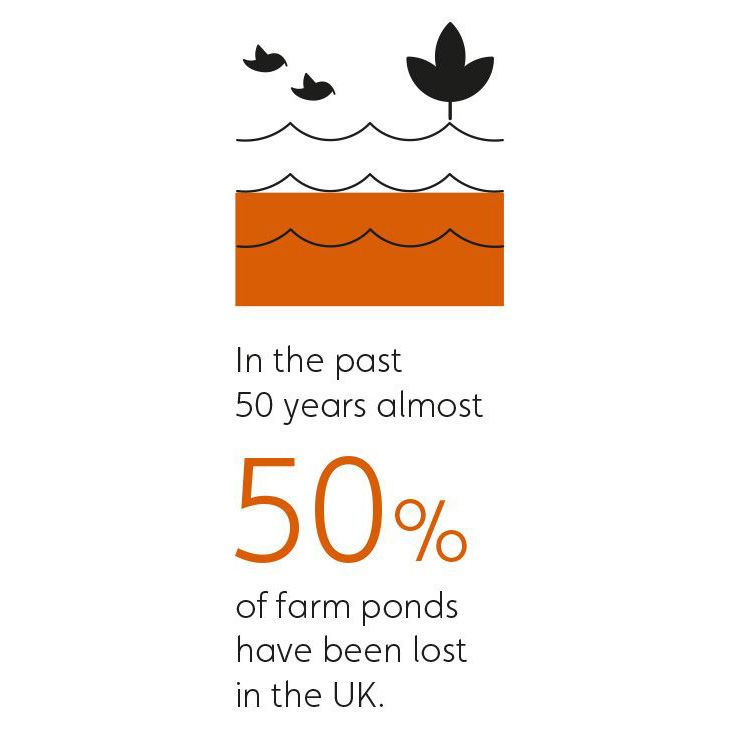

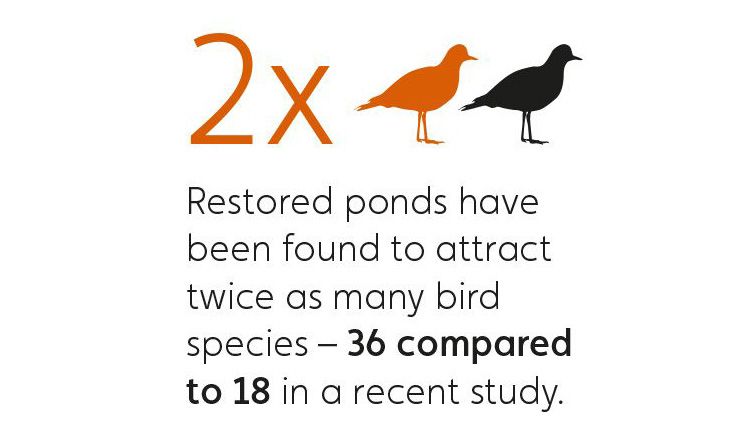

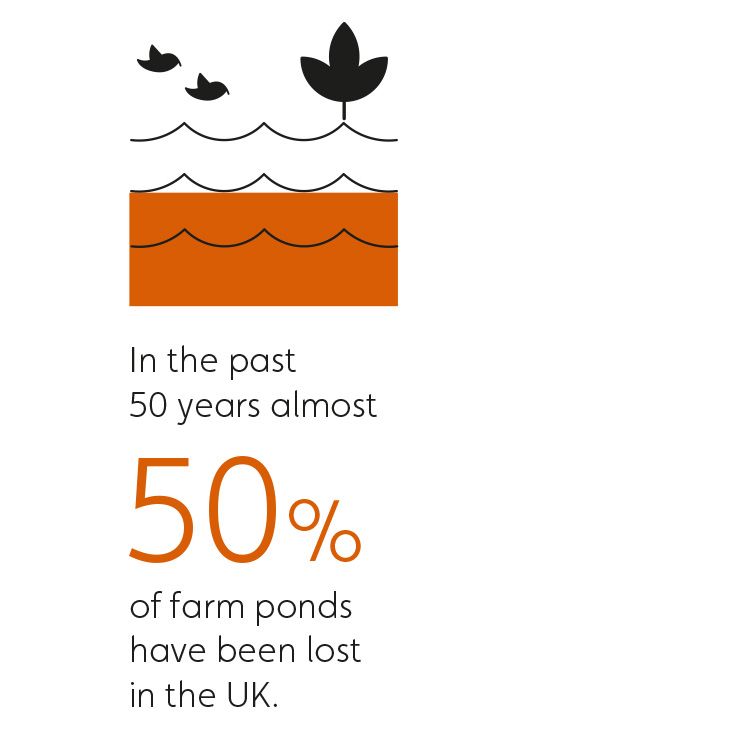

The project also focuses on seemingly isolated patches of wetland such as farm ponds. Conservative estimates suggest that almost half of farm ponds have been lost since 1970.

While some have been filled in to increase land for agriculture, others have just been abandoned and not cared for, like the leaf-filled muddy hollow, choked with brambles and elder bushes, that belongs to Countryfile presenter and farmer Adam Henson. It is quite literally a ‘ghost’ of a pond where all Adam might find these days, if he’s lucky, is the occasional loyal toad. But Adam was determined to bring his ‘ghost’ back to life.

"When you start digging out the leaves and the clay, you feel like you’re being a vandal, but the results will be beautiful."

And once it’s filled with water and the sunlight is no longer blocked by branches, it should again teem with aquatic invertebrates. And these emerging insects will become a ‘service station’ for birds and bats feeding their young throughout spring and summer.

A wetland landscape includes a healthy network of ponds. And they benefit a surprising amount of wildlife, far more than just amphibians and eels. Without them to provide vast quantities of nourishing insects, many species that aren’t usually associated with wetlands struggle to survive.

Digging for otters

Scott Petrek is a man on a mission. He’s knee deep in water, digging out a ditch and as a reserve warden at Slimbridge wetland reserve in Gloucestershire this is all in a day’s work. His goal? To create bigger, better and more connected wetlands. Why? Because Scott knows this is one of the best ways to halt the catastrophic loss of biodiversity that we’re facing across our planet, particularly in our wetlands. By reconnecting wetlands, he’s helping wildlife pass along the corridors of streams and ditches.

"In the last six months we’ve restored and created two miles of ditches. This is great news for wildlife like eels and other migratory fish, as well as birds, dragonflies and of course water voles. It will also be a real boost for the otters that make their home at Slimbridge and across the wider Severn Vale."

A male otter's territory can be up to eleven square miles, so by making more wetlands, connecting them up and encouraging more eels and fish into the area, Scott and his team are making it easier for them to hunt and get around. They’re also enticing them with well-maintained reedbeds, which are popular with otters due to their secluded nature and good fish stocks. Man-made otter holts also help.

"You’re effectively creating an underground chamber, a couple of metres across, with a couple of pipes that come in. You need to make sure the pipes have kinks in, so it doesn’t let the light all the way into the inner chamber, as otters like quite a dark space."

But it’s not always been so easy for otters. During the 20th century the otter declined by 95% of its range in Western Europe. In England, the otter disappeared dramatically with disastrous effects on the wider ecosystem. They were hit by pesticide use and were also hunted for their pelts, up until it became illegal in the 1970s.

The rise of the mink

At the same time as otter numbers were plummeting, American mink were allowed to escape from fur farms in the late 1950s. It then set about trying to live as mink do naturally – which quickly caused havoc.

Otters and American mink may look superficially similar when seen from a distance – and moving fast! Both can swim, which confuses things further.

The mink quickly spread throughout the country, filling the void in the ecosystem left by the otter. It had a disastrous effect on water voles. Unlike the otter, which will eat voles if it can, the smaller mink can enter their burrows, leaving them with little defence, as Scott explains:

"Unlike the mink, the opportunistic otter will hunt a variety of species, catching anything from small sticklebacks to larger eels and perches, meaning it doesn’t pose a direct threat to populations of its prey animals, such as water voles. Water voles can also seek refuge from otters in their burrows."

Even today water voles are the fastest declining UK mammal, and vulnerable to extinction.

The otter fights back

But by the turn of the 21st century, cleaner water and healthier rivers and wetlands were leading to more fish in rivers and lakes and since then otter numbers have gradually increased. By 2011 they had colonised every county in England and every town and city with waterways had populations of otters. Their return heralded a change of fortune for the mink.

An adult dog otter weighs in around 12 kg. As much as a fox and rivalling even the heavy-set badger. If you’re a 1-1.5kg mink, then the lithe, muscular otter makes for a formidable neighbour. Otters can easily outcompete mink for food and territory, and experts have recorded a decline in mink where otters have reclaimed their lost territories. In fact, otters have driven minks so successfully from some areas, that conservation organisations have been able to reintroduce water voles where they’d once been wiped out. It is no coincidence that some of the WWT reserves where otters have returned also support water vole populations.

"The otter is an apex predator, the uncontested king of the wetland."

As such it plays an important part in maintaining a healthy ecosystem and its return means the otter has become a symbol of wetland health.

"It’s a bit like what happened when they re-introduced the wolf into the Yellowstone National Park in America. Otters are like the wolves of the wetlands." says Scott.

And the story has similarities. Historically in the Yellowstone National Park, the loss of wolves meant the elk population grew and they moved around less during winter, browsing heavily on young willow. This was tough on the beaver that needed willows to survive in winter. Now the predatory wolves keep the elk on the move, preventing them from intensely feeding on the willow.

The beaver rediscovered an abundant food source in the willow that hadn’t been there previously. They flourished and built new dams and ponds. Beavers are 'keystone' species, which means their activities govern the lives of other species in the ecosystem. The wetlands they create even out seasonal runoff, store water, provide cold, shaded water for fish and the new robust willow trees provide homes for songbirds.

The introduction of wolves into the Yellowstone National Park, shows how encouraging and re-introducing an apex predator can really effect change in an ecosystem. Like wolves, otters are the apex predator in their wetland habitats and their resurgence is having similar knock-on effects.

As well as keeping invasive species like mink at bay, their presence also ensures no one animal can dominate. And maintaining this balance between predators and prey is vital in ensuring rich biodiversity. If one species becomes too dominant, others suffer.

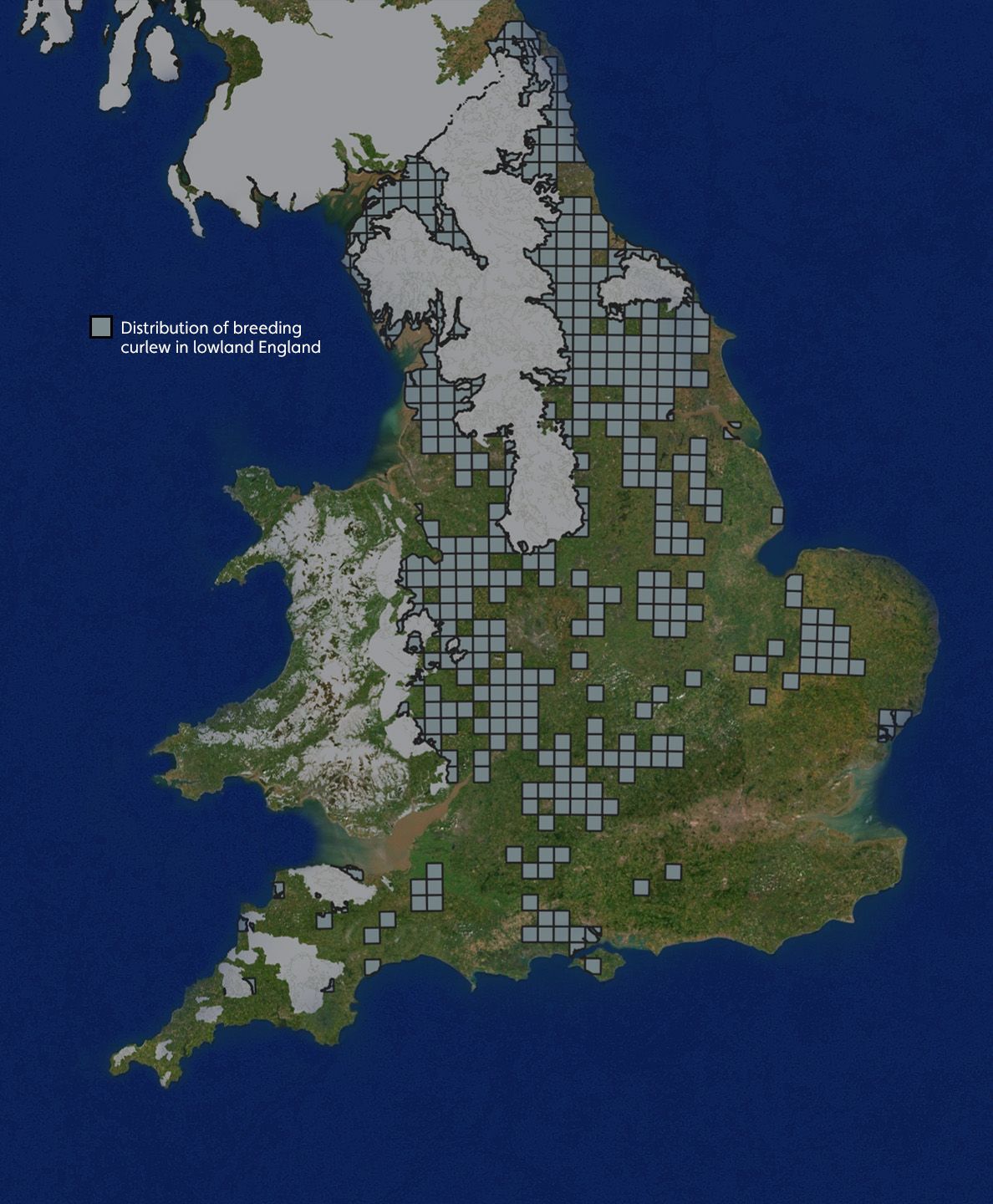

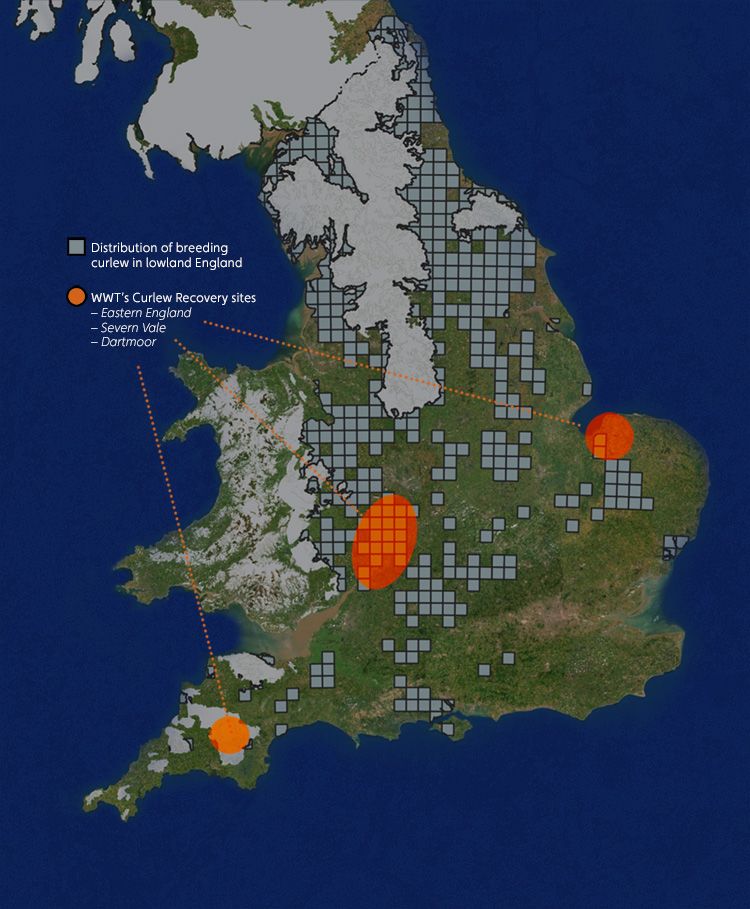

Plight of the curlew

It’s a winter afternoon and the low sun is setting over the Severn Estuary. The call of the curlew drifts across the still water. The haunting call of Britain’s largest wading bird is one of the most evocative sounds of our countryside and has inspired poets and songwriters from Dylan Thomas to Benjamin Britten. Yet there are fears it could fall silent forever.

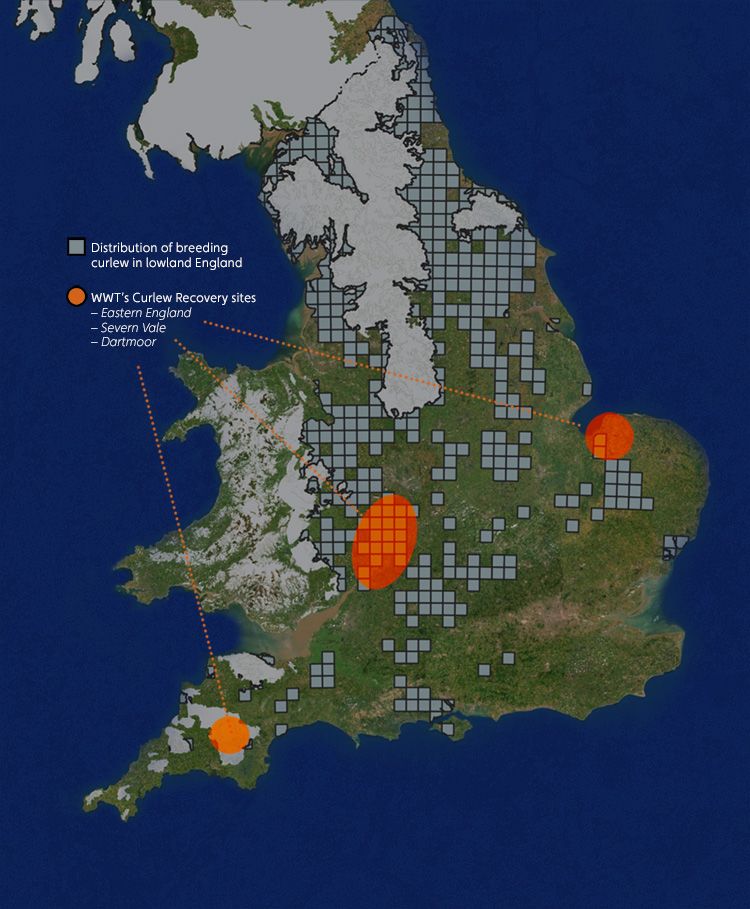

Since the 1970s, the UK has lost 65% of its curlews and it’s now considered the most pressing bird conservation priority in the country. In winter, curlews can be found feeding in the mudflats and saltmarsh of estuaries, but in spring, breeding lowland curlews favour extensive grassland, heaths and bogs - especially wet meadows with long grass.

Unfortunately, these breeding sites are sometimes very risky for the birds: their nests and chicks are vulnerable both to predators and the mowing of grass crops.

And over recent decades, changing agricultural practices has meant that the land has become drier, more uniform and supports fewer insects, making it harder for curlews to find food and raise chicks successfully. So WWT is working in three areas in England to try to reverse curlew decline.

Predator problem?

Generalist hunters like foxes, badgers and crows are also having a major impact, with curlew eggs and chicks an easy target. This is entirely natural predation, but in the modern world, the numbers of some predators are booming. There are several possible explanations for this. For example, our lifestyles provide a lot of food that feeds these predators – leftover food from our bins and high streets, game birds released for shooting, and casualties from our busy road network.

The lack of top predators in the UK is also thought to have had an effect. When present they may have kept the number of middle predators like foxes and badgers down. But whatever the reasons, as curlew expert Mike Smart explains, there’s now simply too much predation for the curlew population to sustain.

"Once upon a time there might have been wolves and lynxes and bears and other things that might have predated on predators like foxes. But there’s not very much that predates on them now. Some predator pressure is probably a natural thing and you wouldn’t want to upset that, but when the predators get to be very common it puts extra stress on other species. We don’t really understand that balance very well."

Bringing biodiversity back to the land

Although providing protection (for example, by putting up fences) can help, the long-term answer lies in considering land-use changes to make the wet meadows safer for birds like the curlew. And to do this, we must work in partnership with those who make their livelihoods from the land.

Gordon Halling is one of the farmers responsible for what is thought to be the largest floodplain hay meadow in England.

"I’m 76 and there’s always been curlews here, but we’ve taken them for granted."

Situated near Tewkesbury, Upham Meadow was recorded in the Domesday Book and still provides grazing and winter feed, much as it would have done a millennium ago, despite the fact that the M5 now runs across it. For Gordon, managing his farmland for curlews hasn't been a struggle.

"WWT and Natural England asked us to make a few changes and mostly it’s been easy, cutting this patch instead of that patch and doing it in three cuttings instead of one, so the curlews have a chance to nest and have some long grass for cover."

Hand reared curlews to the rescue

Changes in land use will be the long-term solution, but in the meantime the population is in freefall. Sometimes, drastic action is needed for the short term.

We’ve recently discovered that curlews like nesting on airfields. They probably enjoy the wide, largely chemical-free expanses of grassland, and the perimeter fences provide protection from some of their predators. Unfortunately these sites are not always a suitable refuge: where they pose a risk to low-flying aircraft, the eggs can be legally destroyed for safety reasons. In 2019, instead of being licensed for destruction, eggs from military airfields in East Anglia were transported to WWT Slimbridge in Gloucestershire where they were hand-reared by conservationists – using a technique called headstarting – and released in the Severn Vale.

Headstarting is a time consuming and labour-intensive job, which involves collecting, incubating, hatching and hand-rearing the eggs. However, by giving these birds a boost at their most vulnerable stage and then releasing them into the wild once they can fly, conservationists can dramatically increase the number of fledglings produced by a population while we search for a more permanent solution. As Nigel Jarrett, Head of Conservation Breeding at WWT explains:

"On one hand, curlews at East Anglian air bases pose a potential risk to aviation, but on the other hand they have the potential to help their struggling cousins in the South West. By babysitting these chicks until they can fly, we can help encourage a new generation of British curlews in the lowlands."

In the UK, the curlew is performing an ‘umbrella’ species role. Many other ground-nesting birds, like lapwing and redshank are also declining because they face similar pressures to the curlew. By gaining a greater understanding of the dangers facing the curlew and the reasons for its drastic decline, conservationists, hand in hand with landowners, can make ecosystem-wide improvements not just for the curlew, but for many other species too.

A flagship for wetlands

The Critically Endangered spoon-billed sandpiper is undoubtedly an appealing bird. Yet with millions of species at risk around the world, some may ask what’s the point of throwing so many resources at one small bird?

In the case of the spoon-billed sandpiper, part of the reason it was chosen for such particular attention is because it represents thousands of kilometres of irreplaceable, threatened wetland habitat.

Why save the spoon-billed sandpiper?

The flyway the sandpiper uses to migrate from its nesting grounds in the Arctic to wintering sites in South East Asia takes it across some of the world’s most threatened wetlands. It’s a route that’s used by millions of other birds. What's more, the sandpiper's charismatic appearance has captured public interest around the world. So, saving the spoon-billed sandpiper is about more than saving just one bird. It’s become both a ‘flagship’ and an 'umbrella' species for conservation throughout the region.

Conservationists have attached satellite tags to a number of sandpipers. The information provided has been invaluable and has helped them identify the wetlands where the sandpipers, and all wading birds along the flyway, stop to rest, feed and moult their feathers in safety. This enables conservationists to prioritise their actions. One such wetland is Jiangsu, in China.

Protecting one of the world’s greatest wetlands

It’s 6am and as the sun rises over the mudflats of the Yellow Sea, Nigel Clark, a scientist with the British Trust for Ornithology joins an exhausted but exalted team of bird catchers as they head to their hotel for some well-earned rest. It’s the end of an intense week, which has seen this forty-five strong team of international scientists work into the small dark humid hours for ten nights in a row to catch and release an extraordinary 1,778 shorebirds, including five spoon-billed sandpipers.

"The whole team has worked phenomenally hard over the last ten days, averaging 16 hours in the field each day, but we were all focused on the conservation goal – to ensure there’s a vibrant ecosystem in the Yellow Sea for all the migrants that pass through it."

Nigel and his colleagues are here as part of an international mission to protect one of the world’s greatest wetlands and the millions of migrating birds that use it.

Lying between mainland China and the Korean peninsula, the Yellow Sea’s 10km wide belt of intertidal coastal mudflats stretches over 2,850m2 and is considered to be the single most important site on these birds’ flyway.

By carrying out surveys like this, scientists are discovering just how rich the biodiversity of this region is. As Nigel explains, it’s now thought that more than 35 species of birds occur here in internationally significant numbers with 17 of them globally threatened like the spoon-billed sandpiper.

"When we first came to the Jiangsu coast, we thought we may catch a small number and might learn a little about the birds that come here. But now after five years, we have ringed around 8,000 birds, of over 30 species. These marked birds have been seen later, on the coasts throughout South East Asia and Australia showing just how pivotal the Jiangsu coast is in the lives of these global travellers."

And it’s this information that is proving crucial in persuading governments to take action to protect these vitally important wetlands from the threats of pollution and reclamation. In 2018, thanks to advocacy work by conservation charities China agreed to commit to no further reclamation in the Yellow Sea.

In 2017, one of the birds’ key wetland sites in the Gulf of Mottama in Myanmar was given international protection as a result of the spoon-billed sandpiper’s growing international profile. This was a win not just for the sandpiper, but for all the other birds, animals and people that rely on it for their survival.

How conservationists are protecting wetlands and their biodiversity

By focusing efforts on wetlands and their wildlife, environmental conservation organisations are not only helping to save individual species from extinction, they’re also helping to rebuild some of the world’s most valuable ecosystems.

"Wetlands are natural super systems that sustain an extraordinary level of biodiversity. We must act now to protect them."

From the mudflats of the Yellow Sea to the ponds of the Severn Vale, wetlands form a giant web, connected by water and by the creatures that rely on them to provide for each stage of their lives. But in a story we’ve seen play out repeatedly across the world, break one connection and the web starts to unravel.

Wetland conservation plays a major role in protecting the planet from further catastrophic loss of biodiversity. And, although the situation is already extremely serious, the good news is that restoring them has proven time and again to bring returns. Compared to habitats with large, slow-growing vegetation such as rainforest and woodland, allowing water back on the landscape and re-connecting wetlands is a cheap and quick way to restore the giant interconnected web that supports all life.

What can I do?

Many organisations are working hard to convince the Government to prioritise nature recovery.

While we do this, there are things we can all do to help boost wetland biodiversity.

Create your own wetland

Creating or restoring a wetland doesn’t have to be done on a huge ‘landscape’ scale to make a difference. Even the humble garden pond can have a huge impact on local biodiversity. There’s lots of advice available on how you can make your garden wildlife friendly just by adding water.

Discover the wonder of wetlands

Wetlands are the sponges of our uplands, the filters in our farmland, and the sinks in our cities. But historically, they've been undervalued and all the good things they do have not been appreciated.

Find out more about these incredibly biodiverse habitats, the threats they face and the benefits they bring to all life, and help us spread the word about wetlands.

Credits

Maps produced using data from Bird Atlas 2007-11 (Balmer et al., 2013), which was a joint project between BTO, BirdWatch Ireland and the Scottish Ornithologists' Club.

Severn Vale Curlew Recovery project is a partnership between WWT, Gloucestershire Naturalists Society and Natural England. It is funded by the project partners, Defence Infrastructure Organisation, Defra, WaderQuest, Marjorie Coote Animal Charities, Saintbury Trust and the generosity of WWT members and appeal givers.

Dartmoor Curlew Recovery Project is a partnership between the WWT, Duchy of Cornwall, Dartmoor National Park Authority, Paignton Zoo, Natural England and RSPB, with funding from the Prince of Wales’s Charitable Foundation, the Duchy of Cornwall, Natural England and the other implementing partners.

Eastern England Curlew Recovery is a partnership between Natural England, Pensthorpe Conservation Trust, WWT, and BTO, with the Defence Infrastructure Organisation and RAF, and funding from Defra and Natural England.