Animals of hope

10 animals bringing stories of hope for our wetlands and their wildlife.

Our wetlands play host to the most extraordinary array of colourful and wondrous wildlife.

Each one has a tale to tell. Of extraordinary lives, epic migrations, feats of endurance, and survival against all odds.

They capture our hearts, spark our imaginations, evoke our sympathy and pique our curiosity. Their heart-warming stories open a window onto their wetland worlds.

The evocative call of the curlew conjures up vast winter estuaries and flower filled summer hay meadows.

While the arrival of our Bewick’s brings tales of wild, remote and frozen wetlands.

As we peer into their lives, these species shine a light on the threats they and their wetland homes face. They also highlight the plight of the other less ‘lovable’ or ‘captivating’ wetland wildlife that WWT is also helping, that live alongside them.

These stories of recovery offer us hope. Hope that by restoring wetlands and unlocking their power, we can offer a solution to the nature crisis we’re facing.

Here are just some of our stories of hope....

1. Curlew

The flower filled floodplain meadows so favoured by curlews are fast disappearing with devastating effects on wildlife. To turn the tide on this destruction, the curlew has become an important focus for our floodplain restoration work.

Curlews rely on our wet grasslands for safe nesting sites. In fact, Britain holds a quarter of the world’s curlew population.

Floodplain meadows also provide places where these ground nesting birds and their young can feast on the invertebrates that live in the meadows' soft, damp soil, ditches and ponds.

Through our Flourishing Floodplains project, we’re working across the Severn and Avon Vales to protect and restore these precious wetlands. We’re digging ponds and creating more wetlands to create bigger, better, more connected floodplain meadows.

We’re using innovative technology like GPS trackers to shine a light on the daily lives of our curlews as they search for nesting sites across the area. Then as the breeding season progresses, we’re using thermal imaging drones to help us locate nests in the long grass.

And in helping curlews, we’re also helping to protect these vital wet grasslands for wider wetland nature, like other wading birds and the European eel.

2. European eel

Ok, so we know the European eel’s not the cuddliest of animals.

But still, who could fail to be amazed by their extraordinary life cycle only made possible by our wonderful wetlands.

Starting life in the Sargasso Sea in the northeast Atlantic, eel larvae make their way to coastal Europe on ocean currents. When they arrive, they transform into elvers and use our estuaries to travel landwards.

They transition to a life in freshwater, swimming through a network of ditches and wetlands throughout a river’s floodplain. Here they’ll grow up to a metre long, sometimes over decades. Finally they return to the sea, to make their way back to their breeding grounds.

In decades gone by eels were once common in European cuisine, for example eel pie in London’s East End. But due to lack of habitat and inaccessible waterways, there’s less of them about. The number arriving in Europe has fallen by around 95% in the last forty years. And because they’re a key part of the food chain, fewer eels means less food for other fish, birds and mammals.

Across the Severn and Avon Vales, we’re working to protect the eel and their wetland habitat. At Slimbridge, we’ve removed barriers for eels and other migratory fish to enter nearby wetlands from the Severn estuary. North of Slimbridge, along the River Frome at Fromebridge Mill, we’ve installed a fish pass enabling many different fish species to navigate around the large weir there, and again upstream at Arundel Mill in Stroud.

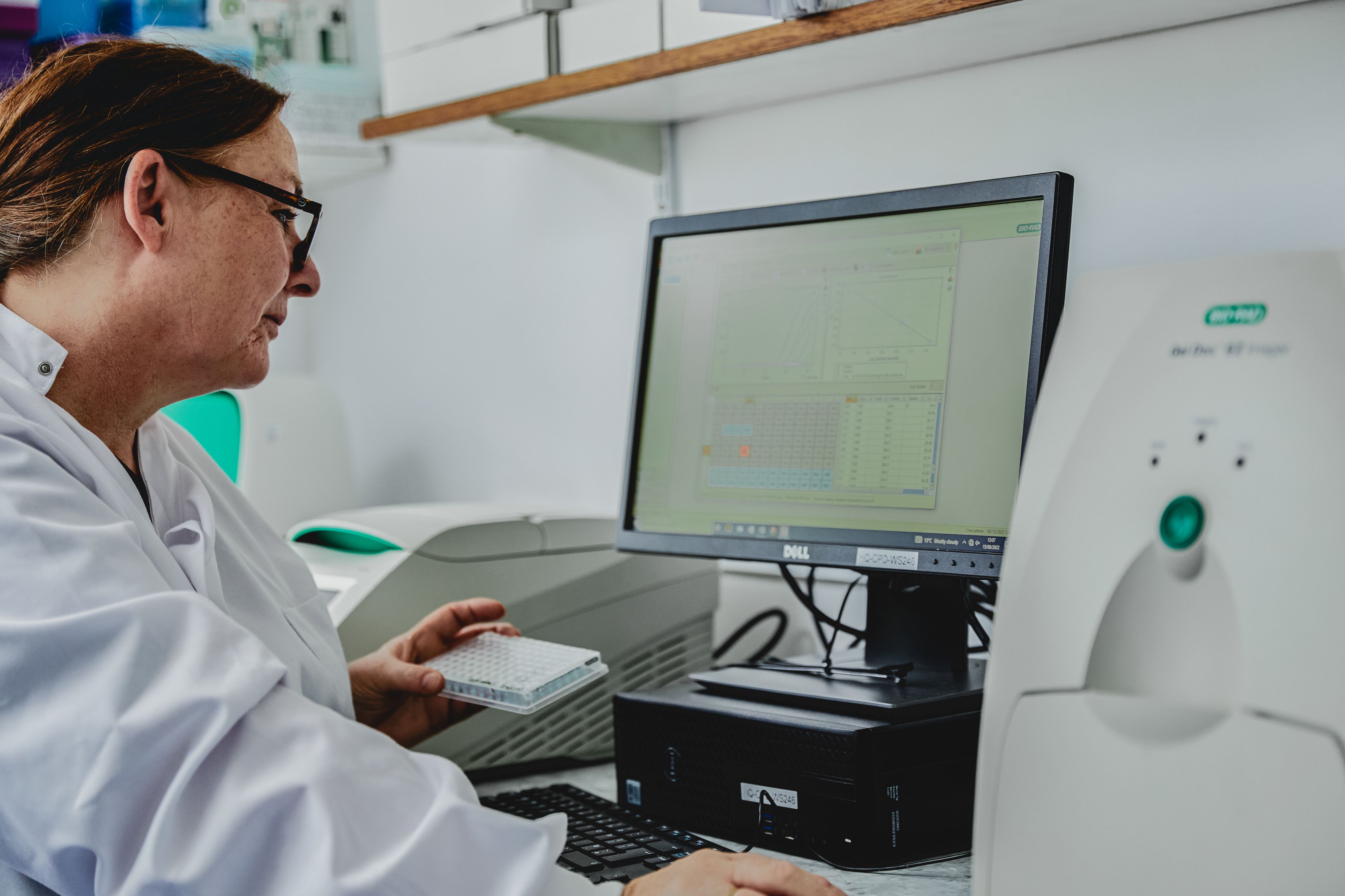

WWT scientists are also using e-DNA to identify trace DNA elements in the environment. It means we can draw up a list of species using a water body. While eels are a key indicator species for a healthy wetland, this research will also help identify other species within the ecosystem.

3. Otter

Otters are always a crowd pleaser at our wetland centres. With their cheeky antics and playful characters, it’s easy to see why they’ve become a charismatic focus for our wetland conservation.

But as a top wetland predator, there’s another reason they’re so important. Their presence helps maintain a healthy ecosystem. Why? The bottom line is our wildlife developed in the presence of these predators. So, it’s to be expected that wetland nature has evolved to thrive in an ecosystem where there are apex predators like otters. This means, by helping otters, we’re also helping create a healthier wetland ecosystem.

Otters can hunt across up to 10 miles of rivers and other waterways to find enough food to live on. So, one of the best ways to support them is by providing bigger, better, more connected wetlands.

We’re restoring and creating ditches across our reserves and removing barriers to encourage more eels and fish into the wetlands. This is making it easier for otters to hunt and move around our wetlands.

We’re also enticing them with well-maintained reedbeds, which they love because of their secluded nature and good fish stocks. We’re also providing man-made otter holts.

Improving the wetlands around our sites is great news for otters. But our work is also benefitting eels and other migratory fish, as well as birds, dragonflies and water voles as well as the whole wider wetland ecosystem.

All going to show why our work helping otters is a great way to help wetlands too.

4. Godwit

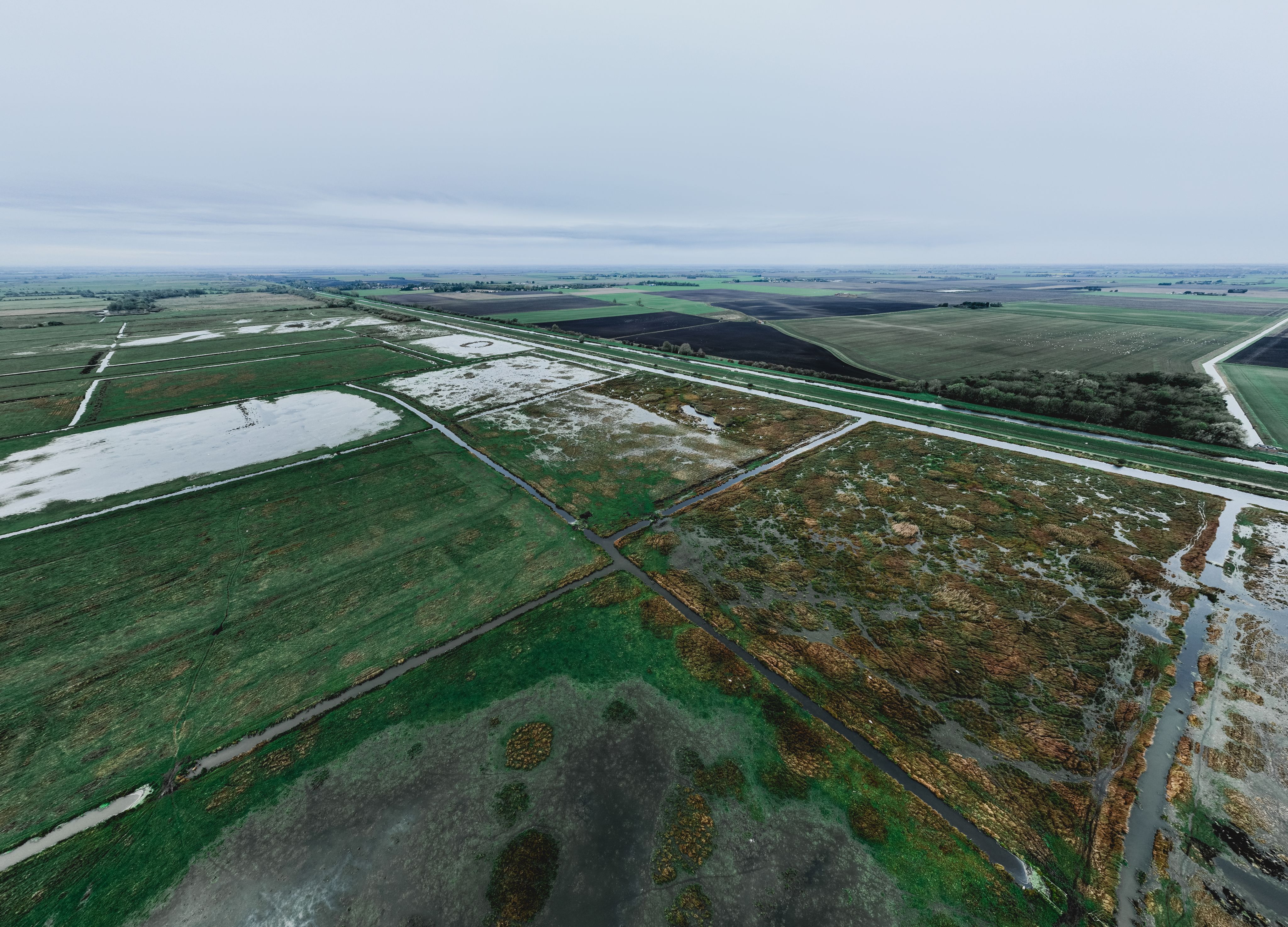

The enigmatic godwit is playing a vital role focusing attention on our important fen habitat.

The UK boasts unique wetlands essential for our waders. Some of the most important are found on the Fens near WWT Welney. Most of the UK’s breeding pairs of black-tailed godwits are found near here on the Ouse and Nene Washes. They migrate here to breed and nest in the wet grasslands. With almost half of Europe’s black-tailed godwits having disappeared in the past 25 years, these birds need our fenlands now more than ever.

As part of our Project Godwit, we’ve restored 300 acres of fen, creating new pockets of wetland homes. We’re also controlling water levels and putting up anti-fox fencing to protect them.

We’ve also boosted chick numbers through a rear and release programme. By using artificial incubation to protect the hatchlings through their first vulnerable days, we’ve been able to fledge three to four chicks from each nest. This is five times more than the birds can manage themselves in the wild.

And it’s not just godwits benefitting from this work. Other waders like greenshank, avocet, lapwing and snipe all make use of the improved wetlands.

5. Willow tit

Fresh from the success of Project Godwit and the restoration of their fenland habitat, we’re restoring wet woodlands or ‘carr’ to help the willow tit. This species is a lover of wet woodlands, nesting in rotting trees. But it’s massively declined in the UK, with a decrease of 83% between 1995 and 2017.

At WWT Washington and WWT Llanelli, we manage wet woodlands to encourage them to continue to breed there. We’re giving this red-listed species a helping hand by installing ‘predator proof’ nesting boxes where the tits can excavate a nest, but woodpeckers can’t access.

By raising the profile of wet woodland and how much has been lost, the willow tit is also helping us support all the other wildlife that lives there too.

6. Natterjack toad

The natterjack toad is much rarer than the well-known common toad. It needs warm, sandy soil in which to live and breed, and ephemeral pools to spawn their strings of eggs.

Sand dunes, heaths and salt marshes like those at WWT Caerlaverock are the natterjack toad's preferred habitat.

We’re helping to conserve their remnant population that lives on Caerlaverock's wide and varied saltmarsh, where they inhabit breeding ponds during the springtime.

Conservation of natterjack habitat benefits a wide range of other species too. From rare plants such as samphire, much sought-after in traditional British cuisine for its salty taste, to a whole range of waterbirds that use this habitat.

Saltmarshes are also of huge benefit to people. They buffer us from storm surges and store more carbon per area than trees.

7. Spoon-billed sandpiper

At first glance, the spoonies' size and stature might suggest they're somewhat small and insignificant.

But what’s been achieved in their name for the vast mudflats and coastal estuaries of East and Southeast Asia is anything but.

The story of their incredible migration has drawn attention to the thousands of kilometres of irreplaceable, threatened wetlands all along their flyway.

For years, very little was known of the spoonies’ secret lives.

We knew they were serious migrators, flying thousands of kilometres up and down the East Asian-Australasian Flyway. Travelling between their summer breeding grounds in arctic Russia to their moulting and overwintering sites in the coastal mudflats of Asia, including the vast delta systems of Southeast Asia.

But all that changed when, with support from partners, we were able to fit them with tiny satellite tags – the smallest of their kind.

Thanks to tagging and surveying efforts, we now have a much clearer picture of where the spoonies are going, which wetlands they are using and where they need protection.

Data from this work has already revealed previously unknown moult sites on the Korean Peninsula. And in 2021 the Getbol tidal mudflats in South Korea joined the UNESCO Natural World Heritage list. A big win for spoonies.

One of our most important discoveries has been in Tiaozini in China. It's now been awarded UNESCO World Heritage Status thanks in part to the tagging and surveying efforts.

In 2008, spoon-billed sandpipers were discovered in the Gulf of Mottama in Myanmar. Subsequent research has shown this is the spoonies' most important overwintering site. In 2017 the Gulf was awarded international protection, promising a better future for spoonies.

Using the spoonies' story, we’ve been able to rally support from governments and communities to provide protection for these crucial coastal wetlands and seek out opportunities to restore them.

It’s great news for spoonies, and for the millions of birds that share their wetlands along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway.

Thanks to the spoonies and their tiny tags, we can now dream of a vibrant wetland ecosystem for all the migrants that pass through the region.

8. Bewick's swan

The Bewick’s swan’s long and perilous migration takes it from its breeding grounds in the far northern Arctic to wintering sites along the estuaries of the UK.

It’s a tragic story of illegal hunting, lead poisoning, and dwindling wetland habitats. Yet this tale of adversity has served as a catalyst, uniting communities, hunters, conservationists and governments across their flyway. Together, we’ve been able to ensure greater protection for the vital wetlands these birds need. And this means more chances of a successful migration, not just for the swans, but for all the other flyway users too.

These wetlands play a pivotal role as essential migration ‘service stations’ for birds of all shapes and sizes. During the summer, many waterbirds and waders breed on the vast high arctic, taking advantage of plentiful food and the wide-open spaces, relatively free from predators and disturbance. As winter approaches, they travel south and west, escaping the advancing snow and ice. The thousands of miles they cover make the wetland stop-over sites along their route indispensable for feeding and resting.

9. Sarus crane

In the vast delta wetlands of Cambodia, numbers of the iconic sarus crane have crashed in the last decade.

Large areas of their wet grassland homes are being destroyed to support the country’s fast-growing economy, with devastating effects on people and wildlife.

Millions rely on the wetlands of the Lower Mekong for freshwater, livelihoods and food.

We’re using the sarus crane to focus attention on the loss of Cambodia’s wet grassland.

We're also working with communities of farmers and fishers, helping them earn a more stable, sustainable income. This means we can protect these wetlands not just for people, but for the sarus crane and the hundreds of other species that depend on this ecosystem too.

10. Madagascar pochard

The Madagascar pochard has become a vital species for opening a window on the work we’re doing restoring Madagascar's wetlands for both wildlife and people.

The Madagascar pochard was once thought lost forever. But in 2006, around 20 were re-discovered, barely surviving on a remote lake.

A mission to save them was launched. Several clutches of pochard eggs were collected and hatched at a conservation breeding facility in Madagascar. By 2018 it would house 100 birds.

To be able to release any of these birds back into the wild, we needed to find a healthy wetland. And that meant restoration at a landscape scale.

Lake Sofia was chosen and WWT began work with local people to improve the lake, for both wildlife and people, through education on sustainable fishing and agriculture.

With a long-term project in place to ensure healthier wetlands for everyone, we were then able to successfully release the pochards onto their new lake.

Bringing life to wetlands

From the vast mudflats and estuaries of Southeast Asia...

...to the flower filled water meadows of the UK...

The wetlands where we work offer incredibly important havens for so much nature.

And in telling the stories of just some of our wonderful wetland characters, we hope to be able to show the huge impact our work is having for all our wondrous wetland wildlife.

© WWT images